Oct 29, 2024 | Events, Roundtables

On Tuesday 8th October, we hosted a roundtable discussion based on the Team of Teams (ToT) ethos, more commonly known from General Stanley McChrystal’s book Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. Published in 2015, the book refers to the concept ‘Team of Teams’, which aims to embed collaborative working across organisations through a web of interconnected teams, based on McChrystal’s experience as commander of the U.S. Joint Special Operations Command.

The purpose of the workshop was to explore the benefits of a Team of Teams approach within a commercial setting and some of the real lived experiences and challenges in managing its roll-out.

We were delighted to welcome two guest speakers:

- Simon Higgens MBE, Business Development Director at STORY Contracting and former Royal Engineer with the British Army

- Scott Murray, Performance and Integration Director at SCS Railways, delivering HS2 London Tunnels

Edward Moore, our Chief Executive, opened the session, providing background into our work and then into the book and its goals: principally around embedding an ethos of collaboration in organisations.

In addition, we shared a Slido poll to gauge the room’s experiences of cultural change in their projects and organisations before delving into the main content, this was later used as a comparison.

Simon opened with an example of his time in the military where he was given command and the goal of achieving a specific objective: Building a positive relationship with an ally.

He had freedom in the nature of the solution but a limited timeframe to design and implement his plan. Simon discussed how in his role he utilised a Team of Teams approach as a natural course of action to achieve results, despite at that point being unaware of the philosophy. He related the six key themes that underpinned his approach:

- Complex over complicated

When Simon first joined the military, it was focused on a hierarchical mindset: telling people what to do and how to do it. This meant that although tasks were complicated, there were clear plans. Over the years, growing complexity and asymmetrical warfare necessitated a shift to an output-based mindset: Focusing on embracing the complexity of a problem and how to achieve results with an adaptable approach over a fixed structure. This required a cultural change to collaboration being the norm – as it is the only way to achieve common aims.

- Unifying purpose

Every person involved in a project should be aware of what the ultimate goal is, understand why they are involved, and how their part relates to that purpose.

This enables teams and individuals to be empowered to make decisions that relate to their area, as they have a common and clear understanding of the ultimate goal.

- Effective delegation

Leaders need to step back and let teams ‘get on with it’. Teams should be built based on expertise, and therefore the team members are the ones who will know their work area and how best to approach tasks to deliver them successfully. Leaders need to be capable of driving strategy and longer-term thinking, managing high-level risks and scanning for upcoming issues.

Trust and communication are imperative for project success, and this must be modelled from the top.

- Adaptable over efficient

Every organisation needs to plan for change – it will happen regardless. Contingencies, mitigations and courses of action need to be thought through carefully as plans will inevitably change as a project progresses.

In addition, this adaptable approach should, again, be embedded as an active mindset in teams: people should be empowered to adapt and change things in the areas they have responsibility over, to serve the project goal.

- Leadership

Teams need to be allowed to grow, make mistakes and learn from them. A focus on ‘superhero leaders’ results in nobody else being taught how to lead, make decisions or develop to take on a responsibility. A spectrum of leadership skills is required, with a focus on understanding your team, their capabilities and skillsets.

Simon talked through how the military focuses on developing individuals’ skills for the next rank they’re aiming for, rather than putting underdeveloped people into roles they’re not yet ready for and hoping they succeed.

Throughout his talk, Simon stressed that the military, while sharing a lot of overlaps with commercial delivery, has a separate focus so not everything applicable in one area will be relevant to the other.

The project that he talked through in the session was ultimately successful, through a focus on the above themes enabling three key outcomes:

- Teams and individuals were allowed to lead in their areas: if they needed assistance, it was there, but he, as the overall leader, didn’t interfere in their specific areas.

- Building the environment for specialists to operate, taking away political interference and enabling them to focus on delivering.

- Leaders could focus on the long-term, strategic view over and above the minutiae of each task, trusting the team to deliver while they ensured objectives would be met.

Following on from Simon, Scott then talked through embedding Team of Teams in a contractual environment. Scott’s focus was on Team of Teams as a set of leadership behaviours that underpin how things are done. Scott imparted that moving to a Team of Teams approach is not a traditional organisational transformation, where boxes are moved around on an organisational chart, but instead represents a cultural change in how people within the organisation are expected to operate.

It also requires a shift in how people think: in implementing Team of Teams in a project organisation, Scott found that many discussions would turn to peoples’ concerns with their specific areas: If one of their SMEs was needed to support a different or more critical area of the business, how would that be budgeted? Would they get reimbursed for the time lost in their area of the project? There was a significant challenge in trying to embed a holistic, ‘best for project’ view over ‘best for me’.

Scott identified a number of key takeaways in implementing Team of Teams:

- Leadership needs to be bought in

Building a Team of Teams environment relies upon trusting people to deliver. This means that leaders need to get used to specifying outcomes over a list of tasks, which can be uncomfortable to those that like to maintain control.

Leaders need to support the embedding of new ways of working and not interfere. Importantly, they need to be focused on long-term thinking. Effective behavioural change across an organisation will not be done within 3 months, but more in the order of 2 years or more.

However, those two years will pass regardless: it is up to leaders whether at the end of it they have an effective, functioning environment or are still facing the same challenges.

- Bad behaviour needs to be dealt with immediately

This must happen from top to bottom. Leaders role model the behaviours that others will follow, so they must visibly demonstrate calling out and challenging behaviours that do not match the agreed or intended ways of working.

The environment you create to deliver your project is an important foundation for delivery. It underpins and supports every other part of the project. It should therefore be high on the agenda and consistently reinforced.

- Test and reinforce communications

To truly build understanding, individuals and teams need to be engaged and reengaged regularly and consistently. It is dangerous to assume understanding from one or two presentations or workshops, you must work with people and test that they understand why the new way of working is the right approach.

The floor was then opened up for discussion. In the following conversations, some themes shone through:

How do we break the cycle of making the same kinds of mistakes that we see so commonly across projects and programmes?

- As humans, we have many biases that inform recruitment, including affinity bias, where we recruit in our image. This is an area where we need to break the cycle to be able to diversify our approaches to delivering the best outcome.

- The right behaviours are just as important as technical competence and should be strongly considered in the hiring process, particularly for leadership roles – but following on from above, this needs to be properly designed so that “the right behaviours” are not simply “someone who thinks the same way as I do”!

- We need to have a system in the industry of training, educating and developing people to lead effectively. Graduate/apprentice schemes with 6-month placements are a good start, but after those initial 2-3 years nobody is ever again provided with this cross-industry experience.

- Change needs to be accepted and embedded as a constant over ‘business as usual’. We intrinsically know this to be true and many of us can resonate from experience: what was new 20 years ago is old and stale now. We need to set ourselves up to deliver in a changing environment rather than plan for change as an additional activity.

Is there a ‘critical mass’ of people required in a project organisation to embed the Team of Teams approach?

Team of Teams is more about a way of working, culture and behaviours, so should be applicable in any environment, from a small team to a whole army. However, the bigger the organisation, the more difficult it will be to embed. Leaders must be engaged: if they aren’t, it will fail. Scott suggested that if a proposal to utilise a Team of Teams approach doesn’t have active support from at least two-thirds of the leadership team, it may be better to scale back, focus on a smaller part of the organisation or project and make it work before attempting to go bigger.

The roundtable also highlighted some things that major projects and programmes in infrastructure can learn from other industries and areas, and the importance of considering behaviours and ways of working in project delivery.

A key theme that came out was the concept of “who is in your phone book?” – i.e., who do you contact when you need a problem resolved – and who do they contact? These are the people you want in your ‘team of teams’: the subject matter experts and problem solvers.

This needs to be tempered, however, by not just defaulting to the same people – this technique promotes using an existing network over either training new people or embracing diversity of thought.

The Slido poll also gave some positive results in that almost 75% of those present stated that their teams were enabled to make decisions and implement them, and the vast majority stating that they believed in long-term culture over short-term goals.

These are not new issues, extending back to the Latham Report in 1994 (and earlier!), however, the industry has historically struggled to come to terms with them. The collected experiences of the leaders and experienced professionals in the room show that perhaps there is a cultural change already underway that may support the long-term thinking and trusted, delegated decision-making that the industry needs to harness.

The roundtable posed some great insights into Team of Teams from the perspective of our speakers and guests, with great discussion had. We’d like to thank everyone who attended and encourage you to keep an eye out for next year’s programme of events. View our event calendar here.

Aug 21, 2024 | Events, Roundtables

On Tuesday 9th July, ResoLex hosted a roundtable discussion featuring Concordis International; a peacebuilding charity that uses dialogue to support the development of sustainable relationships among communities involved in or affected by armed conflict. The event was led by Peter Marsden, Chief Executive of Concordis International, and Edward Moore, Chief Executive of ResoLex and Chairman of Concordis International. The event allowed industry professionals to explore the complexities of building resilient and sustainable relationships in challenging environments. By drawing on lessons from the third sector, particularly in conflict negotiation, the session aimed to equip participants with strategies to enhance collaboration and resilience in the major projects industry.

The roundtable began with a thought-provoking question; if we can manage conflict and develop collaborative relationships between armed groups, then why do we struggle on major projects?

Peter opened by describing his work directly alongside those involved in, or affected by, armed conflict and how he helps to find collaborative, workable solutions that address the root cause. Similarly, in the major projects industry, there is an understanding of the need to develop collaborative working environments, yet we can often struggle to understand how to establish them. Providing an example, Peter shared his firsthand experience of meeting with a leader of an armed group. The leader arrived with 100 armed and angry individuals, creating an intense atmosphere, where Peter quickly needed to establish an escape route. Through the story, he came to the realisation that he was not in control, and emphasised the importance of meeting on the leader’s terms and relinquishing some of his power to establish trust and develop a relationship with the group.

Peter asked two people to join him for a demonstration. The two participants stood back-to-back and were given a scenario: denounce your partner and go free, stay loyal and receive one year in prison, but if both denounced, they got a five-year sentence. One participant denounced, while the other remained loyal, illustrating the complexities of trust and betrayal. The demonstration highlighted the impact of communication and on decision-making, as participants can learn from past experiences, understand each other’s behaviours, and build trust over time, creating expectations between the individuals involved.

Peter highlighted that each war comprises of a million decisions, influenced by incentives, constraints, opportunities, and threats. The goal is to convince people to adopt a long-term view of their relationships and move away from the instant gratification mindset prevalent in many projects. By understanding and influencing incentives, and addressing constraints, we can guide behaviours towards more collaborative and sustainable outcomes.

Peter’s stories underscored the importance of four key themes:

- Trust-Building: Meeting on others’ terms and understanding their perspectives are essential in creating trust and not creating power struggles.

- Communication and Repeated Transactions: Effective communication and repeated transactions can shift dynamics from adversarial to cooperative.

- Decision-Making in Conflict: Every conflict involves numerous decisions, each influenced by various factors. Understanding these can help create positive incentives and discourage negative behaviours.

- Long-Term View: Adopting and encouraging a long-term view is crucial for fostering trust and cooperation. The ability to communicate and anticipate future interactions can alter dynamics, promoting collaboration over conflict.

Relating Peter’s key themes to the major projects industry, Edward highlighted four key connections:

- Timeframe Orientation: Emphasis was placed on understanding how timeframes influence operations and relationship development. Unrealistic timelines often lead to negative behaviours and culture. Setting up projects and programmes with realistic timeframes is essential for success.

- Dispute Escalation Mechanisms: Effective systems allow for differences to be resolved in a positive manner before escalating into conflict. Upfront agreements and structured planning help navigate complex environments and prevent disputes.

- Horizon Scanning: Quick recognition of issues through horizon scanning and a ‘sense-and-react’ model of action is vital for proactive problem-solving.

- Collaborative Environment: Creating the right environment, where people feel safe and empowered, is crucial for effective collaboration.

Regardless of the industry, there were some key takeaways to enhance collaboration and resilience:

- Creating Systems and Processes: Establishing systems and processes that enable a good culture and safe environment for key conversations enhances collaboration. Additionally, creating systems for dealing with conflicts, such as dispute resolution mechanisms, is essential. Trust in these systems and the people involved is crucial.

- Trust and Culture: Building trust and a positive culture within projects and programme can change the perspective from short-term to long-term, altering incentives accordingly.

- Safe Environment: Creating a safe environment for key conversations and proactive planning is essential for long-term success.

The development of strategies to enhance collaboration and resilience should consider some key questions, such as:

- To what extent can the people we are working with take a long view rather than a short-term view?

- How can we ensure effective communication to alter dynamics positively?

- What mechanisms can we implement to foresee and address potential issues without falling into optimism bias?

The roundtable highlighted the relevance of game theory and the Prisoners’ Dilemma in the major projects industry, emphasising the need for a long-term perspective, effective communication, and systematic relationship management. The event highlighted the importance of trust, structured planning, and proactive issue identification in achieving sustainable outcomes, as well as creating a safe environment for key conversations and changing incentives to significantly enhance collaboration and resilience in complex environments. By integrating these lessons, industry professionals can build resilient, collaborative relationships and navigate complex environments more effectively.

View our event calendar for information on upcoming roundtables and other events.

Apr 26, 2024 | Events, Roundtables

On the 23rd of April, we welcomed Roseanne Serrelli, Partner at Sharpe Pritchard for a discussion on how contracts can be used to help embed collaborative behaviours on complex projects.

The session was opened by our Chief Executive, Edward Moore, who gave the attendees an overview of the evening and an introduction to the topic.

Ros began her presentation by explaining that the terms used in these ‘collaborative contracts’, e.g. alliances, enterprises, partnerships – have no specific legal definition. Any individual party involved with the contract is likely to interpret these terms differently. The key when looking to develop a contract which supports a collaborative endeavour is to focus on attention on the purpose of the relationship, rather than the term used. This approach has the benefit of shifting the focus away from risk transfer and instead puts the focus on risk avoidance and resolution.

The level of collaboration built into a contract can therefore be bespoke based upon the need, rather than starting with a pre-populated document. Options exist along on a spectrum from a light-touch arrangement to full alliances with shared legal risk, reward and finances. When developing a contract, it is worth thinking of the options as a menu from which the appropriate provisions can be selected based upon what the client intends to achieve.

Ros talked through several examples of different collaboration systems in existence, some of which have been discussed at previous ResoLex roundtables:

- Project 13 – not a contract itself, but an ecosystem and ethos for delivery that focuses on achieving outcomes rather than on the inputs.

- NEC Alliance – a single contract to which all are parties, including the client. This often works better on an ongoing programme with repeatable work, where the goal is to incentivise shared responsibility. This is more difficult on single projects where there may be more single points of failure that cannot be shared easily between participants.

- X12 – An option within NEC contracts that seeks to support multi-party collaboration, including containing a common set of objectives for all parties.

- FAC1 – An overarching framework that sits above individual contracts and contains items that need to be supported by those contracts, such as early warning systems.

Regardless of the form of the contract, there were some key takeaways about what is needed to ensure collaboration can be effectively supported:

- A defined governance structure with clear roles and accountabilities (often in a RACI matrix) – make it straightforward for people to understand who is doing what in the contract environment (and be clear that accountability is not the same as liability!)

- A clear decision-making process – the process may evolve over the lifetime of a project or differ in different parts of a programme, but it needs to be set out clearly and communicated to everyone involved.

- Set up Core Groups and Boards – these do not need to be over-engineered. They should have clearly defined objectives and discussion/decision points.

These structures provide a foundation for a successful collaboration. Having a contract that does not enable the environment you want will undermine your project from the start, though equally, having the perfect contract is meaningless if people do not engage in the right ways of working.

The contract underpins the practical side of collaboration; namely regarding people and their behaviours. When setting up for success, the behaviour of the joint team will be a key factor in how the benefits of these structures and processes are maximised in the project or programme environment.

The development of appropriate ways of working should consider some key questions, including but not limited to:

- Will the arrangement require co-location or jointly employed resources?

- What is the communications strategy? Will there be joint messaging from all parties? Will there be common branding and a ‘united front’ when facing the public?

- What are the processes for change or bringing in new people?

- What is the process for sub-contracting? Does the client need to approve any additions?

- How is the project insulated from outside noise (e.g. political pressures) to enable the team to focus on delivering the outcome?

- What do you do when things go wrong? It cannot be assumed, even with the perfect contract and the best people for the job, that there will never be an issue or point of contention between the parties. Provisions should be included in the agreement to enable parties to exit as necessary. Though counterintuitive, Ros shared that her experience is that providing clarity about the exit process provides comfort to the parties and in fact, often encourages parties to stay in contract and work through the challenges.

The session closed with a stimulating discussion on what needs to be done to try to build more collaborative environments in projects and programmes and how contracts can facilitate that, recognising that they are usually the starting point for the relationship. Points were raised in the room on the importance of ‘selling’ the benefits of this approach, particularly to clients when setting up a project and to politicians who may be overseeing major schemes. The conversation was a good reminder of the need to take the time to clearly define the required outputs and outcomes of a scheme before diving in, in order to set up the contract and environment that best facilitates these outcomes.

Oct 18, 2023 | Events, Roundtables

Last week, we were delighted to be joined by Professor David Mosey CBE for an update and lessons learned since the launch of the FAC-1 Framework Alliance Contract.

Ed Moore opened the session, commenting that David had first introduced the FAC- 1 Framework to the ResoLex audience at a previous roundtable event in February 2018. It was therefore heartening to see the traction the framework has achieved over the last five years.

David began his presentation by explaining that the FAC-1 is a multi-party framework alliance contract that integrates the procurement and delivery of one or more different projects, with the ability to connect multiple contracts awarded to each collaborative team member. It creates the ability to establish the relationships and systems that the parties wish to use to embed collaborative ways of working, supporting the achievement of improved value, risk management and dispute avoidance.

So far, the contract has been adopted on the procurement of over £100 billion of contracts, ranging from smaller £5 million projects and SME consultant alliances to the £60 billion contractor/ consultant/ supplier procurements of the Crown Commercial Service.

Some of the key features of the FAC-1 contract are as follows:

- Creates a bridge that integrates multiple project appointments and operates in conjunction with multiple FIDIC, JCT, NEC and PPC forms

- Allows alliance members to include the client, any additional clients, an in-house or external Alliance Manager and any combination of selected consultants/ contractors/ suppliers/ providers, with the facility to add additional alliance members

- Enables the planning and integrating of a successful alliance, setting out why the alliance is being created, and stating agreed objectives, success measures and targets, with agreed incentives if these are achieved and agreed actions if they are not achieved

- States how work will be awarded to alliance members, under a direct award procedure and/or competitive award procedure and under early standard form orders

- Describes how the alliance members will seek improved value through shared alliance activities, including a collaborative system for engaging with tier 2 and 3 supply chain members

- Describes how risks will be managed and disputes avoided, using a shared risk register, core group governance, early warning and options for an independent adviser and alternative approaches to dispute resolution

- Provides the flexibility to include particular legal requirements and special terms required for any sector and in any jurisdiction.

David highlighted a number of different examples where FAC-1 has been used successfully, and one of the best examples came from the Ministry of Justice.

New Prisons complex project alliance

The UK Ministry of Justice (MoJ) created an FAC-1 Alliance to procure their £1.2 billion new prisons programme. The alliance integrates the work of ISG, Kier, Laing O’Rourke and Wates as contractor alliance members, with Mace as alliance manager, and supports their use of BIM and Modern Methods of Construction to agree on optimum designs and strategic relationships with key tier 2 supply chain members.

MoJ report that their FAC-1 new prisons alliance has meant they have been able to use the alliancing process both as a contract form and as the means to structure the relationships. This approach helped to embed the collaborative relationship early, from the alliance launch to the transition through the different phases. Each of the four contractor alliance members nominated representatives from their organisation to sit alongside representatives from the MoJ and its other delivery partners (Mace, WT Partnership and Perfect Circle). Together, they formed the Core Group, establishing strong leadership and trust from the outset.

One of the highly positive outcomes of the use of FAC-1 has been greater cost certainty and cost savings. MoJ reported that these included:

- Fees for the pre-construction collaboration phase finalised at the tender stage

- Direct fees (overheads and profit) and staff preliminary rates fixed at the tender stage

- Projected duration and contract value based on previous prison builds at HMP Five Wells and Glen Parva

- Pre-construction supply chain collaboration to build up cost certainty and savings by transparent supply chain engagement for key or critical packages on all four prisons i.e., mechanical, electrical, and plumbing engineering, pre-cast concrete, and cell windows and doors.

Final thoughts

The final message from David was that recent evidence suggests that more public sector clients are starting to look at alliancing as a beneficial method of procuring major projects and programmes of construction work. Alliancing does however require a significant shift in both mindset and behaviours, where each of the parties involved is intent on working collaboratively over a prolonged period to achieve win-win gains. In the absence of an agreed set of processes and structured agreements, there is a tendency to revert to short-term transactional behaviours.

The advantage of FAC-1 is that it provides a set of highly flexible mechanisms which are easy to set up, and then provides the programme leadership with the processes needed to create effective relationships.

You can find the round-up from the first FAC-1 roundtable on our website here: https://resolex.com/events/resolex-roundtable-building-a-supply-chain-alliance/

For anyone thinking of using the FAC-1 contract, David has written a handbook which helps clients, contractors and advisors think through some of the practical aspects of implementing the framework. You can purchase it here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/FAC-1-Framework-Alliance-Contract-Handbook/dp/1913019837

Jul 12, 2023 | Events, Roundtables

Last week, we were delighted to welcome three guest speakers from Jacobs to the ResoLex Roundtable: Jessica Ellery, Gail Hunter, and Joshua Weatherley. Jacobs is a full-spectrum professional services firm including consulting, technical, scientific and project delivery with a workforce of about 60,000 people worldwide.

The evening was introduced by our Associate Director, Kelachi Amadi-Echendu, who provided some background to the ResoLex Roundtables and how the event links with our values as a business. Our Chief Executive, Edward Moore then introduced the topic, reminding us that whilst collaboration in itself may be very nice, if it doesn’t improve productivity, one has to question the point! At ResoLex, we see projects as comprising three primary areas of expertise: technical, commercial, and social. We believe that the key elements are interlinked, and the social component is inextricably linked to project performance. During the session, Ed highlighted our model, and expanded on the need to take an integrated approach to the three elements in order to achieve project success.

Jess, Josh and Gail explored the topic through the lens of a live giga project that is in its early stages of delivery in Saudi Arabia. A perspective offered was that perhaps the scale and longevity of such programs offered the chance to truly embed an effective, collaborative social system, even more so than the opportunity we have in the mega-project environment. The presentation began with a poignant safety moment, and then an introduction to four immense projects in the Neom region of Saudi Arabia. Each of these projects are hugely ambitious, the most dramatic being The Line. The Line is a revolution for urban living, which according to the plans will be 500m tall, 200 meters wide and a staggering 170km in length. Whilst a project of this scale is fascinating in itself, the evening’s platform served as the backdrop to a much broader discussion around the challenges of working in such a complex programme environment. Throughout the session, Josh and Gail prompted the audience with a range of engaging questions and themes designed to stimulate debate (a dangerous thing to do with a ResoLex audience!).

The presentation identified the challenges created by the multiple interfaces that must be managed by the teams and explained that this becomes exponentially more difficult to cope with as size and scale increase, supporting the initial introduction and highlighting the need to therefore factor in behaviours when setting the project strategy. This stimulated a lengthy discussion in the room around the more nebulous concepts of leadership and project culture, there was a common agreement that paying attention to these areas early in the programme is a critical success factor. It was also noted that one of the reasons for the poor performance of mega projects, in general, is the lack of ability for many project leaders to scale up from large projects, and when faced with high levels of complexity, they tend to fall back on simplistic solutions which inevitably fail in more complex and challenging environments.

So, what are the conclusions from the evening’s discussion? Here are our top five takeaways:

- There is a need to ‘operationalise’ collaborative intent. In other words, major projects (and especially giga projects) need to focus on establishing the policies and processes that will embed the principles of collaborative ways of working throughout the programme, rather than limiting the discussion to senior management.

- Focus on the active steps needed to build a positive culture, avoiding the default tendency to revert to transactional behaviours as soon as the project comes under pressure.

- The risk management process needs to acknowledge behavioural risk and recognise that effective inter-team relationships are both a risk and an opportunity.

- Relationship management plans should be a compulsory part of the early planning process and should focus on identifying the critical interfaces that need to be mapped and managed.

- Project leaders need to be trained specifically in the practical tools and techniques that will enable them to make the right decisions when working in highly ambiguous and complex environments.

The session closed with reference to the work of Edgar Schein, and his observation that for successful teams, people need to build ‘Level 2 relationships’ with their colleagues. This level of relationship is where we know enough about the people we work with on a regular basis to be able to see them as human beings, rather than just human ‘resources’, who carry out a functional role.

Overall, it was another stimulating and educational evening, with a wide range of views and opinions. As we see projects and programmes becoming ever more ambitious in their scale and desired outcome, the session is a reminder (should we need it!) that planning, setting up and mobilising for success from the start makes life considerably easier for the teams trying to deliver downstream.

If you’d like to join our next Roundtable, please keep an eye on our events page or sign up for our LinkedIn events newsletter.

Mar 10, 2023 | Events, Roundtables

The discussion yesterday evening focused on the Private Sector Construction Playbook, a best practice guide published in November 2022. We were joined by two guest speakers, Alison Cox, Managing Director of Sir Robert McAlpine London Charles Horne, Project Director of British Land and, ResoLex Chief Executive Edward Moore.

Our Principal Consultant, Kelachi Amadi-Echendu began the session, by describing the journey from the government’s Construction Playbook to today’s Private Sector Playbook. She explained how the themes from the ResoLex publication ‘Changing Behaviours in Construction: A Complement to the Construction Playbook’, apply not only in the public sector but also to private sector projects and programmes, to enable improved delivery and better outcomes.

“Historically, the UK construction industry has been characterised by a lack of openness, poor productivity and a failure to invest in innovation”.

Foreword, Trust and Productivity The Private Sector Construction Playbook, November 2022

With many years of experience in the sector, driving excellence and delivering complex and challenging solutions for clients, we were delighted to have Alison Cox join us. Alison began explaining that the Private Sector Playbook was created by the construction productivity taskforce, a working group of developers, contractors, suppliers and professional service providers from the private sector whose underlying purpose is to try and improve productivity in the construction industry. She noted that whilst productivity had improved in a number of sectors, construction productivity had actually declined by 0.6% in the last 20 years. The document was designed to complement the Public Sector Construction Playbook that was released in 2020, taking cues from the public sector whilst understanding the challenges faced by the private sector.

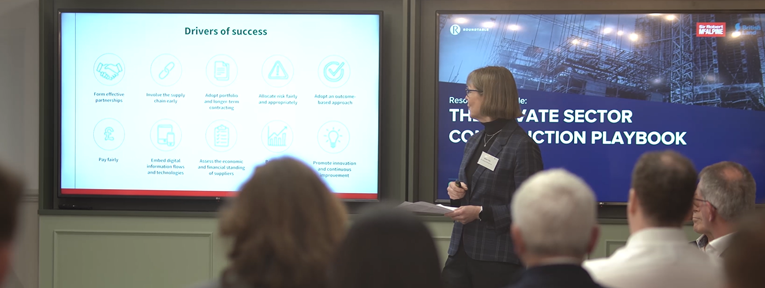

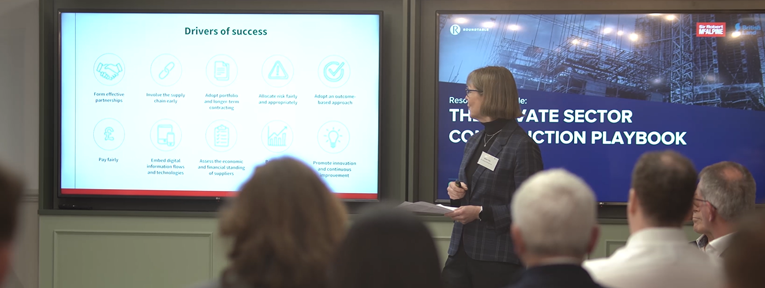

The Playbook is structured around ten key drivers for success, as illustrated in the diagram below. It is interesting to note that half of these focus on culture and behaviours. Alison emphasised the need to concentrate on building the right relationships, particularly at the beginning of a project. She mentioned her own experiences on the construction of the Bloomberg offices where key members of the different teams sat in close proximity in a co-located office. This was a project that was quite dynamic and required the team to be highly adaptable to changes in requirements. The strength of relationships established in the early phases of the project enabled the teams involved to focus on ‘best for project’ decisions, rather than solutions which might be best for individual organisations.

Charles observed the many changes in the construction industry since his experiences working on sites in the mid-1980s, as illustrated by the massive shift in safety that now exists compared to forty years ago. He highlighted the cultural change around health, safety and wellbeing, which simply did not feature when he first began his career. His primary observation is that projects are delivered by people rather than by technology or process. His recent experiences are drawn from Broadgate, where British Land is developing seven consecutive significant buildings under the Broadgate Framework. His starting point for creating the development strategy was the recognition that the customers for these properties are the local users in the area, and as such, care needs to be taken to avoid creating major disruption as the construction works to proceed. Charles’ approach required working with partners rather than suppliers, and so, in a significant break from traditional procurement practices, British Land has entered into a 10-year framework agreement with Sir Robert McAlpine. The framework enables British Land to reduce the risk of multiple concurrent projects and promotes consistency, continuity and innovation.

Contractual mechanisms aside, Charles, focused from the start on establishing an underlying ethos for the programme, based on the principles of Trust, Honesty and Collaboration. These principles have been developed into a set of rules, which every individual involved in the projects are expected to follow. The rules are generally self-policed, and there are very few instances where they are not applied by the numerous teams engaged in the programme. Charles identified a critical role that leadership plays in establishing a successful culture, recognising that in a collaborative contract, leaders need to be skilled at building ‘followership’.

He recognised the challenges of complexity and used the analogy of a pebble dropping into a pond and creating small waves. As projects grow in size and scale, leaders must deal with the challenge of lots of pebbles, dropping into the pool at the same time each creating ripples which intersect and disrupt with each other. He agreed with Alison that co-location is a critical factor in building cohesive and collaborative teams and is fundamental to building teamwork and understanding.

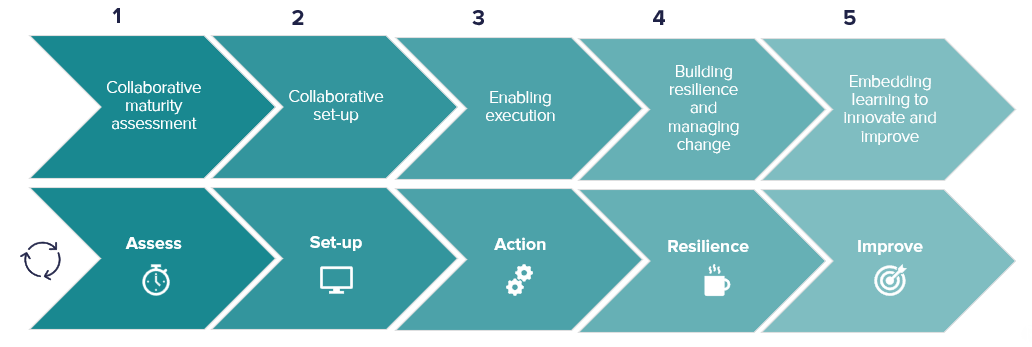

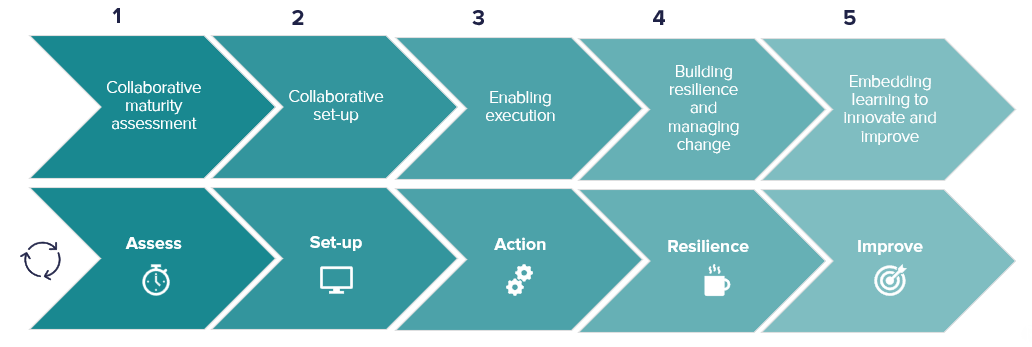

Ed Moore identified the need to establish the right culture from the start, quoting Abraham Lincoln, who said ‘give me six hours to chop down a tree and I would spend the first four sharpening the axe’. Ed made the case that programmes should treat relationship development as a distinct and separate workstream with its own targets and deliverables. Ed observed that too many project leaders tend to assume that their teams will naturally form into collaborative teams and therefore ignore the opportunity to shape the behaviours which occur at the very start. Ed also highlighted the need for project and programme teams to introduce a framework to help teams structure their workstream, and gave an example of the ASARI framework created by ResoLex as illustrated below:

Some of the key points of the discussion from the floor, were as follows:

- Project culture is directly linked to the quality of leadership.

- A critical skill for project leaders is to learn to listen to other points of view rather than press on with their sole perspective as to how a problem should be solved.

- The time for the individual heroic project director has passed. The role of the project director is now to build leadership throughout the team.

- The primary barrier to industry-wide adoption of the Private Sector Playbook remains a driver amongst many clients to appoint the lowest tender, thus propagating the bad habits, behaviours and relationships that inevitably emerge from such practices.

- The key to wider adoption must be to focus on being able to clearly articulate the difference between value over cost and use the successes of previous projects to persuade others to continue to support a route based on effective relationships.

As a final comment, Charles pointed out that on Broadgate, each of the individual projects is still negotiated within the framework. He nevertheless observed that not one contractual letter has yet been issued by either party throughout the delivery of the programme. As he put it, when a difficult issue arises it is ‘our’ problem, not just ‘your’ problem. This is a great illustration of collaboration working in practice.

You can find the featured publications linked below: