Nov 28, 2024 | News and insight

Exploring the importance of values

Collaboration has become a buzzword in the world of major projects and programmes – on trend, and frequently used, but usually without tangible explanation. So, what does it really mean in practice?

At ResoLex, we think of collaboration simply as helping teams work more effectively together to deliver desired outcomes. We work with leadership and project teams on developing collaborative and integrated ways of working, designing and implementing effective strategies to manage interfaces, and monitoring and measuring cultural maturity and behavioural risk.

We’re starting this series, ‘Collaboration is key, but how do you do it?’ to explore the ways in which teams can actually embed their collaborative intent project-wide. Our first area of focus is: Creating a values-based culture.

The importance of values for building and nurturing a positive project culture

Major projects are rarely afforded sufficient time for mobilisation and setup, with political, leadership and stakeholder pressures more often than not, driving a focus on ‘getting spades in the ground’ to show some semblance (or illusion) of site progress. Time and budget constraints only add to such pressures, and collectively, these factors can mean leaders miss important opportunities to build strong foundations and set their teams up for success, especially when it comes to culture, values and behaviours.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, values are “the beliefs people have, especially about what is right and wrong and what is most important in life, that control their behaviour” . Our values help guide our decision-making, help to provide us with a sense of comfort and belonging, and help us connect with others, and to our organisations. In the project environment, meaningful values that resonate with people can encourage teams to connect, demonstrate desired behaviours, and make decisions that best support the desired outcomes and ways of working of the project or programme.

But why bother with project values when the individual organisations that make up a project almost always have their own?

Project values can help:

- Create alignment:

- Drive focus on strategic objectives: In project environments, sometimes it can be a challenge to shift mindsets away from individual organisational goals, towards a project-centric focus. Co-created project values support that effort, and aligning project values with the project’s strategic objectives encourages every action, decision, and behaviour to contribute to achieving the project’s vision. This shared focus helps to unify efforts, build team cohesion and maintain clarity.

- Foster cooperation and collective success: Meaningful values can help foster a sense of mutual responsibility, with team members feeling a sense of belonging and purpose as they contribute to the project’s success.

- Consistent communication: Genuine, meaningful values can become a framework of sorts – a routemap that sets out how we do things around here, the attributes we value, and the way we talk to one another. Actively using the project’s values can support consistent and respectful communication internally within the team, and externally with stakeholders and customers, promoting trust, reliability and clarity.

- Promote a positive environment:

- Encourage positive behaviours: When values reflect the project and are co-created, there’s a stronger sense of ownership and accountability amongst the team. People feel more committed to upholding the values and behaving in alignment with them. Shared values foster respect, openness, and psychological safety. This leads to a more supportive atmosphere where team members feel valued, stress is reduced, and performance and productivity enhanced. This doesn’t mean that the project environment is free of conflict – it means that diversity of thought and healthy conflict are encouraged, and the best decisions are made.

- Drive motivation and engagement: A values-driven culture creates a sense of shared purpose and belonging, which in turn boosts motivation. A strong sense of belonging has been proven to drive greater engagement and productivity.

- Enhance resilience and adaptability: In a project environment, challenges and setbacks are inevitable and can be dramatic in scale, cost and/or impact. Shared values demonstrated by all – especially those in leadership – and especially when in crisis, help to provide a clear sense of purpose, and a guiding light during difficult times. This can help the team remain focused and balanced as they work through the problems.

- Enable and empower quick decision-making:

- Consistent decision-making: Values can help provide guidance for decision-making that aligns with the project’s long-term vision and principles. They act as anchors and behavioural guides that help keep decisions grounded in the project’s core objectives.

- Minimise conflict: When the team shares the same values, it becomes easier to work through differences and keep focused on collective success.

- Facilitate empowered decision-making: Values help to empower team members to be confident that their choices align with the projects core values.

At ResoLex, we work with many of our clients to co-create, embed and nurture values in major project teams, so we were already believers. But recently, the importance of values was really brought to life when we took our team to visit Align JV at their South Portal site.

Site visit: Align Joint Venture

The Align joint venture consists of three international and privately-owned infrastructure companies; Bouygues Travaux Publics, Sir Robert McAlpine, and VolkerFitzpatrick, who together, are constructing the Central 1 package of the UK High Speed 2 line (HS2). Their scope includes delivering the record-breaking Colne Valley Viaduct – which is the longest railway bridge in the UK, as well as constructing HS2’s longest twin-bore tunnel at 10 miles long.

We recently had the pleasure of visiting Align at the South Portal site, hosted by Head of Engagement & Compliance, Darielle Proctor and Stakeholder Engagement Specialist and Community Engagement Lead, Duncan Fallon.

Although we haven’t worked on this specific part of the HS2 project, we have supported the project in many other areas, and we were thrilled to be invited to the site to see the record-breaking works in action, and learn more about the JV renowned for their culture, collaboration, and ways of working.

Although we haven’t worked on this specific part of the HS2 project, we have supported the project in many other areas, and we were thrilled to be invited to the site to see the record-breaking works in action, and learn more about the JV renowned for their culture, collaboration, and ways of working.

Align have overcome some substantial geographical, environmental and technical challenges throughout the project, and have worked through the challenges thanks in part to their strong team culture.

Initially identifying a difference in culture and ways of working between their respective parent organisations, Align JV understood the need to create a one-team culture and an integrated project tea

m. They created values that supported the overall vision of the client, HS2, and brought together the partner organisations, including supply chain and they worked tirelessly to embed and nurture them until they became norms.

From the beginning of our visit, our team were surrounded by a feeling of community, identity and belonging. The values adorned on the side of the building as you drive in and across their sites were role-modelled by everyone we came across, from driver to receptionist to site supervisor. Our conversations with the team underscored the importance of good leadership and project champions, of cultural training and awareness, and of the value of a supportive, trusting client team. The commitment to collaboration and a values-based culture shone through in all aspects of delivery, from recruitment and training, to internal and external communications, and of course the physical working environment – on-site and in the office.

The values of safety, respect, integrity, excellence, and collaboration held by Align encourage a culture of inclusion and collaboration, and all accounts seem to be working!

Thanks for having us!

Darielle Proctor, head of engagement and compliance, said:

“It was a pleasure to show the Resolex team how we do things at Align and the lessons we’ve learnt along the way. We have made real effort to make sure that our culture at Align is engaging and empowering and that our values and associated behaviours drive our day to day interactions and project delivery. They are now part of who we are, what we do and how we do it!

“I believe that our success and ongoing commitment of the Align team is down to the emphasis we have continuously placed on the project culture and creating an integrated project team.”

Keep an eye on our LinkedIn page for the next instalment in the series.

Oct 31, 2024 | Events

Last month, a few of the ResoLex team attended the ICE’s Reimagining Delivery Models: a Panel Discussion on the Future of Project 13 and Beyond lecture. After a welcome from Julio Lacorzana, Manager in Infrastructure & Capital Projects Advisory at Deloitte, the evening presented an opportunity to hear thoughts from the panel of speakers:

- Florence Julius, Director in the Infrastructure and Capital Projects Advisory Team at Deloitte;

- Richard Lennard, Executive Commercial Director at New Hospital Programme;

- Liz Baldwin, Director of the Southern Integrated Delivery Alliance at Southern Renewals Enterprise;

- Andrew Page, Head of Commercial Services at Anglian Water Services.

Andrew and Richard were invited to give some reflections from their experiences of implementing Project 13 approaches at Anglian Water and on the New Hospital Programme, respectively, ahead of a panel discussion and Q&A with all four speakers. We have taken some time to capture a summary of our team’s key takeaways from the evening.

Andrew Page explained that Anglian Water is using an integrated framework approach and is part of an alliance that has heavily relied on Project 13 principles to deliver success. Andrew also stressed that the key focus for an integrated team is on outcomes, not outputs along the way. Andrew explained that after many years of learning through alliancing, Anglian Water understood that the commercial approach is key. Setting up the right commercial approach to incentivise the desired collaborative behaviours underpins the achievement of successful outcomes. Andrew’s statement that “what delivers outcomes is relationships” resonated deeply with our experience of working with project and programme delivery teams.

Richard Lennard began his talk by introducing the New Hospital Programme and its aims and objectives, and he recognised the tension between local and national challenges and requirements that needs to be managed through the programme. Richard explained how the programme is developing a new approach to delivering hospital infrastructure, bringing greater value by developing an ‘Enterprise of Enterprises’ mindset with a supplier and contract ecosystem. The mindset will focus on the following principles:

- Longevity – building long-term relationships

- Parity – no one has all the answers, everyone comes to this as an equal

- Trust – hear everyone’s voices and solutions

- Alignment of outcomes – patient first

The panel discussion and Q&A time posed many insightful thoughts into the future of delivery models, here are some of our key takeaways:

- It is important to assign risk to the right owner whilst also insuring parties work together to develop risk solutions.

- Project teams have a better chance of success when the mindset is ‘if one fails, we all fail’.

- Having a purpose and aligned goals and objectives is crucial, particularly across multiple organisations. This shouldn’t be assumed, and time and effort need to be spent on getting it right.

- Not everyone can work in a more ‘collaborative’ environment. Be mindful of who is asked to do so and whether they can fulfil what might be required of them.

- We need to create a safe space for people to challenge behaviours.

- The client has to own the outcome, acknowledging that you are the most invested party as a client, but also recognising that you can’t do it on your own. Partnering rather than contracting in a traditional manner can help build the right environment for this, where each partner wants to help the other to be successful.

- Consistent, visible commitment is needed from the top of organisations to make any ethos work. Senior engagement cannot happen on a solely one-off basis – behaviour breeds behaviour.

- It’s a symbiotic relationship. You rely on each other to get things done.

- Test the relationships regularly, especially over a long period.

- Be prepared and adaptable to change the way things work. As an example, a Capable Owner should be able to say, ‘I’ve got this wrong, we need to make a change’.

- It is very important to map the governance. Collaborative models are successful when they get the balance right between governance and freedom.

Oct 29, 2024 | Events, Roundtables

On Tuesday 8th October, we hosted a roundtable discussion based on the Team of Teams (ToT) ethos, more commonly known from General Stanley McChrystal’s book Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. Published in 2015, the book refers to the concept ‘Team of Teams’, which aims to embed collaborative working across organisations through a web of interconnected teams, based on McChrystal’s experience as commander of the U.S. Joint Special Operations Command.

The purpose of the workshop was to explore the benefits of a Team of Teams approach within a commercial setting and some of the real lived experiences and challenges in managing its roll-out.

We were delighted to welcome two guest speakers:

- Simon Higgens MBE, Business Development Director at STORY Contracting and former Royal Engineer with the British Army

- Scott Murray, Performance and Integration Director at SCS Railways, delivering HS2 London Tunnels

Edward Moore, our Chief Executive, opened the session, providing background into our work and then into the book and its goals: principally around embedding an ethos of collaboration in organisations.

In addition, we shared a Slido poll to gauge the room’s experiences of cultural change in their projects and organisations before delving into the main content, this was later used as a comparison.

Simon opened with an example of his time in the military where he was given command and the goal of achieving a specific objective: Building a positive relationship with an ally.

He had freedom in the nature of the solution but a limited timeframe to design and implement his plan. Simon discussed how in his role he utilised a Team of Teams approach as a natural course of action to achieve results, despite at that point being unaware of the philosophy. He related the six key themes that underpinned his approach:

- Complex over complicated

When Simon first joined the military, it was focused on a hierarchical mindset: telling people what to do and how to do it. This meant that although tasks were complicated, there were clear plans. Over the years, growing complexity and asymmetrical warfare necessitated a shift to an output-based mindset: Focusing on embracing the complexity of a problem and how to achieve results with an adaptable approach over a fixed structure. This required a cultural change to collaboration being the norm – as it is the only way to achieve common aims.

- Unifying purpose

Every person involved in a project should be aware of what the ultimate goal is, understand why they are involved, and how their part relates to that purpose.

This enables teams and individuals to be empowered to make decisions that relate to their area, as they have a common and clear understanding of the ultimate goal.

- Effective delegation

Leaders need to step back and let teams ‘get on with it’. Teams should be built based on expertise, and therefore the team members are the ones who will know their work area and how best to approach tasks to deliver them successfully. Leaders need to be capable of driving strategy and longer-term thinking, managing high-level risks and scanning for upcoming issues.

Trust and communication are imperative for project success, and this must be modelled from the top.

- Adaptable over efficient

Every organisation needs to plan for change – it will happen regardless. Contingencies, mitigations and courses of action need to be thought through carefully as plans will inevitably change as a project progresses.

In addition, this adaptable approach should, again, be embedded as an active mindset in teams: people should be empowered to adapt and change things in the areas they have responsibility over, to serve the project goal.

- Leadership

Teams need to be allowed to grow, make mistakes and learn from them. A focus on ‘superhero leaders’ results in nobody else being taught how to lead, make decisions or develop to take on a responsibility. A spectrum of leadership skills is required, with a focus on understanding your team, their capabilities and skillsets.

Simon talked through how the military focuses on developing individuals’ skills for the next rank they’re aiming for, rather than putting underdeveloped people into roles they’re not yet ready for and hoping they succeed.

Throughout his talk, Simon stressed that the military, while sharing a lot of overlaps with commercial delivery, has a separate focus so not everything applicable in one area will be relevant to the other.

The project that he talked through in the session was ultimately successful, through a focus on the above themes enabling three key outcomes:

- Teams and individuals were allowed to lead in their areas: if they needed assistance, it was there, but he, as the overall leader, didn’t interfere in their specific areas.

- Building the environment for specialists to operate, taking away political interference and enabling them to focus on delivering.

- Leaders could focus on the long-term, strategic view over and above the minutiae of each task, trusting the team to deliver while they ensured objectives would be met.

Following on from Simon, Scott then talked through embedding Team of Teams in a contractual environment. Scott’s focus was on Team of Teams as a set of leadership behaviours that underpin how things are done. Scott imparted that moving to a Team of Teams approach is not a traditional organisational transformation, where boxes are moved around on an organisational chart, but instead represents a cultural change in how people within the organisation are expected to operate.

It also requires a shift in how people think: in implementing Team of Teams in a project organisation, Scott found that many discussions would turn to peoples’ concerns with their specific areas: If one of their SMEs was needed to support a different or more critical area of the business, how would that be budgeted? Would they get reimbursed for the time lost in their area of the project? There was a significant challenge in trying to embed a holistic, ‘best for project’ view over ‘best for me’.

Scott identified a number of key takeaways in implementing Team of Teams:

- Leadership needs to be bought in

Building a Team of Teams environment relies upon trusting people to deliver. This means that leaders need to get used to specifying outcomes over a list of tasks, which can be uncomfortable to those that like to maintain control.

Leaders need to support the embedding of new ways of working and not interfere. Importantly, they need to be focused on long-term thinking. Effective behavioural change across an organisation will not be done within 3 months, but more in the order of 2 years or more.

However, those two years will pass regardless: it is up to leaders whether at the end of it they have an effective, functioning environment or are still facing the same challenges.

- Bad behaviour needs to be dealt with immediately

This must happen from top to bottom. Leaders role model the behaviours that others will follow, so they must visibly demonstrate calling out and challenging behaviours that do not match the agreed or intended ways of working.

The environment you create to deliver your project is an important foundation for delivery. It underpins and supports every other part of the project. It should therefore be high on the agenda and consistently reinforced.

- Test and reinforce communications

To truly build understanding, individuals and teams need to be engaged and reengaged regularly and consistently. It is dangerous to assume understanding from one or two presentations or workshops, you must work with people and test that they understand why the new way of working is the right approach.

The floor was then opened up for discussion. In the following conversations, some themes shone through:

How do we break the cycle of making the same kinds of mistakes that we see so commonly across projects and programmes?

- As humans, we have many biases that inform recruitment, including affinity bias, where we recruit in our image. This is an area where we need to break the cycle to be able to diversify our approaches to delivering the best outcome.

- The right behaviours are just as important as technical competence and should be strongly considered in the hiring process, particularly for leadership roles – but following on from above, this needs to be properly designed so that “the right behaviours” are not simply “someone who thinks the same way as I do”!

- We need to have a system in the industry of training, educating and developing people to lead effectively. Graduate/apprentice schemes with 6-month placements are a good start, but after those initial 2-3 years nobody is ever again provided with this cross-industry experience.

- Change needs to be accepted and embedded as a constant over ‘business as usual’. We intrinsically know this to be true and many of us can resonate from experience: what was new 20 years ago is old and stale now. We need to set ourselves up to deliver in a changing environment rather than plan for change as an additional activity.

Is there a ‘critical mass’ of people required in a project organisation to embed the Team of Teams approach?

Team of Teams is more about a way of working, culture and behaviours, so should be applicable in any environment, from a small team to a whole army. However, the bigger the organisation, the more difficult it will be to embed. Leaders must be engaged: if they aren’t, it will fail. Scott suggested that if a proposal to utilise a Team of Teams approach doesn’t have active support from at least two-thirds of the leadership team, it may be better to scale back, focus on a smaller part of the organisation or project and make it work before attempting to go bigger.

The roundtable also highlighted some things that major projects and programmes in infrastructure can learn from other industries and areas, and the importance of considering behaviours and ways of working in project delivery.

A key theme that came out was the concept of “who is in your phone book?” – i.e., who do you contact when you need a problem resolved – and who do they contact? These are the people you want in your ‘team of teams’: the subject matter experts and problem solvers.

This needs to be tempered, however, by not just defaulting to the same people – this technique promotes using an existing network over either training new people or embracing diversity of thought.

The Slido poll also gave some positive results in that almost 75% of those present stated that their teams were enabled to make decisions and implement them, and the vast majority stating that they believed in long-term culture over short-term goals.

These are not new issues, extending back to the Latham Report in 1994 (and earlier!), however, the industry has historically struggled to come to terms with them. The collected experiences of the leaders and experienced professionals in the room show that perhaps there is a cultural change already underway that may support the long-term thinking and trusted, delegated decision-making that the industry needs to harness.

The roundtable posed some great insights into Team of Teams from the perspective of our speakers and guests, with great discussion had. We’d like to thank everyone who attended and encourage you to keep an eye out for next year’s programme of events. View our event calendar here.

Aug 21, 2024 | Events, Roundtables

On Tuesday 9th July, ResoLex hosted a roundtable discussion featuring Concordis International; a peacebuilding charity that uses dialogue to support the development of sustainable relationships among communities involved in or affected by armed conflict. The event was led by Peter Marsden, Chief Executive of Concordis International, and Edward Moore, Chief Executive of ResoLex and Chairman of Concordis International. The event allowed industry professionals to explore the complexities of building resilient and sustainable relationships in challenging environments. By drawing on lessons from the third sector, particularly in conflict negotiation, the session aimed to equip participants with strategies to enhance collaboration and resilience in the major projects industry.

The roundtable began with a thought-provoking question; if we can manage conflict and develop collaborative relationships between armed groups, then why do we struggle on major projects?

Peter opened by describing his work directly alongside those involved in, or affected by, armed conflict and how he helps to find collaborative, workable solutions that address the root cause. Similarly, in the major projects industry, there is an understanding of the need to develop collaborative working environments, yet we can often struggle to understand how to establish them. Providing an example, Peter shared his firsthand experience of meeting with a leader of an armed group. The leader arrived with 100 armed and angry individuals, creating an intense atmosphere, where Peter quickly needed to establish an escape route. Through the story, he came to the realisation that he was not in control, and emphasised the importance of meeting on the leader’s terms and relinquishing some of his power to establish trust and develop a relationship with the group.

Peter asked two people to join him for a demonstration. The two participants stood back-to-back and were given a scenario: denounce your partner and go free, stay loyal and receive one year in prison, but if both denounced, they got a five-year sentence. One participant denounced, while the other remained loyal, illustrating the complexities of trust and betrayal. The demonstration highlighted the impact of communication and on decision-making, as participants can learn from past experiences, understand each other’s behaviours, and build trust over time, creating expectations between the individuals involved.

Peter highlighted that each war comprises of a million decisions, influenced by incentives, constraints, opportunities, and threats. The goal is to convince people to adopt a long-term view of their relationships and move away from the instant gratification mindset prevalent in many projects. By understanding and influencing incentives, and addressing constraints, we can guide behaviours towards more collaborative and sustainable outcomes.

Peter’s stories underscored the importance of four key themes:

- Trust-Building: Meeting on others’ terms and understanding their perspectives are essential in creating trust and not creating power struggles.

- Communication and Repeated Transactions: Effective communication and repeated transactions can shift dynamics from adversarial to cooperative.

- Decision-Making in Conflict: Every conflict involves numerous decisions, each influenced by various factors. Understanding these can help create positive incentives and discourage negative behaviours.

- Long-Term View: Adopting and encouraging a long-term view is crucial for fostering trust and cooperation. The ability to communicate and anticipate future interactions can alter dynamics, promoting collaboration over conflict.

Relating Peter’s key themes to the major projects industry, Edward highlighted four key connections:

- Timeframe Orientation: Emphasis was placed on understanding how timeframes influence operations and relationship development. Unrealistic timelines often lead to negative behaviours and culture. Setting up projects and programmes with realistic timeframes is essential for success.

- Dispute Escalation Mechanisms: Effective systems allow for differences to be resolved in a positive manner before escalating into conflict. Upfront agreements and structured planning help navigate complex environments and prevent disputes.

- Horizon Scanning: Quick recognition of issues through horizon scanning and a ‘sense-and-react’ model of action is vital for proactive problem-solving.

- Collaborative Environment: Creating the right environment, where people feel safe and empowered, is crucial for effective collaboration.

Regardless of the industry, there were some key takeaways to enhance collaboration and resilience:

- Creating Systems and Processes: Establishing systems and processes that enable a good culture and safe environment for key conversations enhances collaboration. Additionally, creating systems for dealing with conflicts, such as dispute resolution mechanisms, is essential. Trust in these systems and the people involved is crucial.

- Trust and Culture: Building trust and a positive culture within projects and programme can change the perspective from short-term to long-term, altering incentives accordingly.

- Safe Environment: Creating a safe environment for key conversations and proactive planning is essential for long-term success.

The development of strategies to enhance collaboration and resilience should consider some key questions, such as:

- To what extent can the people we are working with take a long view rather than a short-term view?

- How can we ensure effective communication to alter dynamics positively?

- What mechanisms can we implement to foresee and address potential issues without falling into optimism bias?

The roundtable highlighted the relevance of game theory and the Prisoners’ Dilemma in the major projects industry, emphasising the need for a long-term perspective, effective communication, and systematic relationship management. The event highlighted the importance of trust, structured planning, and proactive issue identification in achieving sustainable outcomes, as well as creating a safe environment for key conversations and changing incentives to significantly enhance collaboration and resilience in complex environments. By integrating these lessons, industry professionals can build resilient, collaborative relationships and navigate complex environments more effectively.

View our event calendar for information on upcoming roundtables and other events.

Jul 28, 2024 | Events

On the 5th of June, we facilitated an interactive workshop in partnership with the Major Projects Association (MPA) and welcomed Manon Bradley, Development Director at the MPA and Emma-Jane Houghton, a commercial specialist with over 20 years of experience in the public and private sectors.

We had an exceptional turnout, with over 50 industry professionals, to explore the impact of leadership in delivering successful outcomes through major projects, specifically the role of clients and delivery team leaders. The interactivity of the session sought to interrogate our beliefs around project leadership and encouraged us to challenge the assumption that clients always know best.

Edward Moore, our Chief Executive, began the session by taking ideas for the punch line to the workshop title. Some of the more coherent responses included “…and created a RACI”, “…and asked one another what was happening”, or “…and appointed a delivery partner”.

Manon then spent a few minutes highlighting the key themes from the MPA report ‘No More Heroes’ which was published last year. The report focuses on leadership capability and the need to address how major projects and programmes are led. Emma-Jane then followed, with her views on the concept of the ‘Incomplete Client’. Her intention was to challenge our existing notions around the role of the client in a major project, and encourage an alternative way of thinking about how we can work together to drive improvements in the way projects are delivered.

Emma-Jane’s observations are based on the recognition that project delivery in the modern world is immensely complex and requires us to step back and rethink the approach to being an effective client:

It is my view that our current understanding and approach to clienting is 2D in a very much 5D world. Clienting has become outdated and is not well matched to today’s spectacularly complex environment and all its rich possibilities – especially the pace of change, challenges, and ambiguity. We spend too much of our industry’s energies stuck in the problems of today pointing at poor performance and lamenting the lack of supply chain investment rather than upping our clienting game.

There were two group activities undertaken during the workshop with the first being to identify activities within the project lifecycle that require leadership. The group were then asked to assign which organisation might be best placed to lead these elements. For example, defining the commercial strategy might be best placed with the Client, but resource management would be led by the Delivery Partner. They then provided explanations as to why these were the best organisations to lead and possible barriers to the identified organisation leading the element. This gave the delegates the opportunity to explore whether the client (or more commonly expected leader) is the right leader for the job or whether the responsibility could be best placed elsewhere. This exercise also allows room for discussion on the types of qualities needed for each leadership role.

The second activity was to take the activities identified in the first exercise and map them across to the project lifecycle. Delegates were then asked to use the Cynefin Framework (pronounced kuh-nev-in) which was developed to help leaders understand their challenges and to make decisions in context. By distinguishing different domains (the subsystems in which we operate), the framework helps recognise that our actions need to match the reality we find ourselves in different phases, through a process of sense-making. The outcome of the exercise was to reevaluate the leadership role and showed that during the life of a project the leader’s ‘baton’ changes hands depending on the phase the project is in and the capabilities required.

During the workshop, the participants were asked to respond to a number of questions to gather their thoughts before and after the exercises. Having analysed the outputs produced by each of the groups and the poll responses, we have been able to pull some interesting insights:

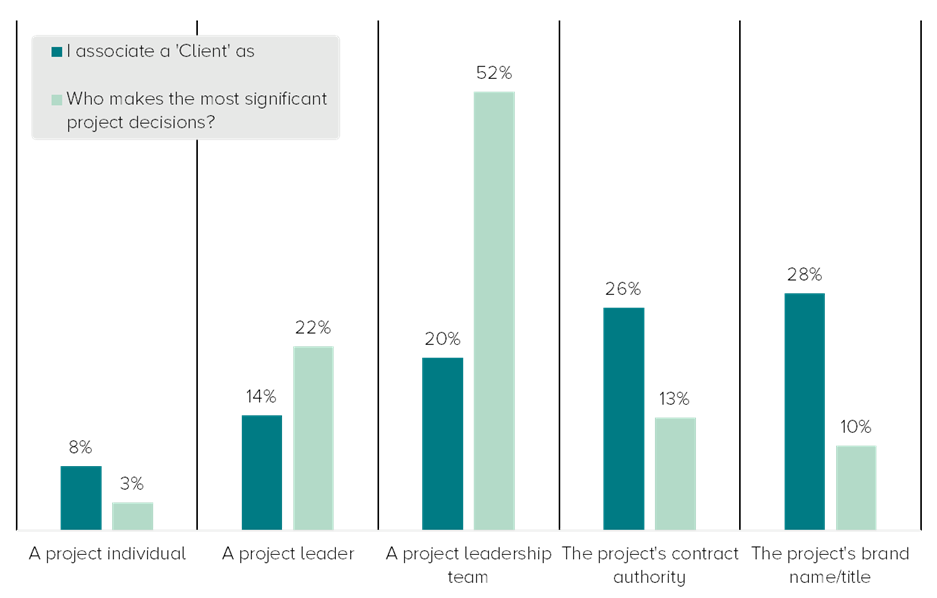

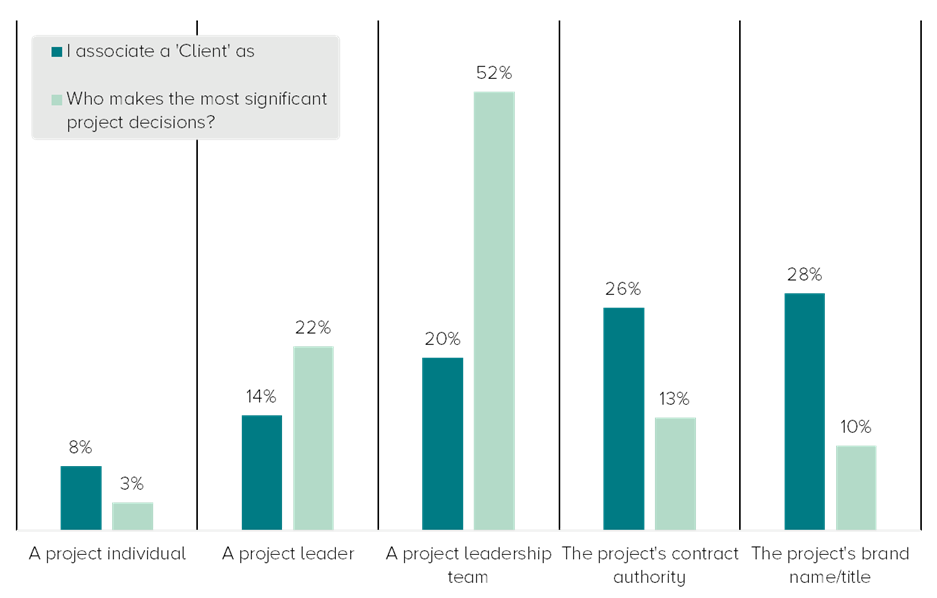

1) There was a highly diverse split of who the Client was perceived to be, supporting the notion that the term ‘Client’ is not fully understood and requires work to clarify and cohere

2) 52% of respondents believed that project decisions were controlled by the project leadership team which demonstrated that the majority see decisions are being governed and driven by the client’s appointed SLT

3) Over 80% of respondents associated the term ‘Client’ with positive qualities, with a strong correlation towards EQ (emotional quotient) centric skills which indicated a preference for softer, less autocratic methods of project delivery

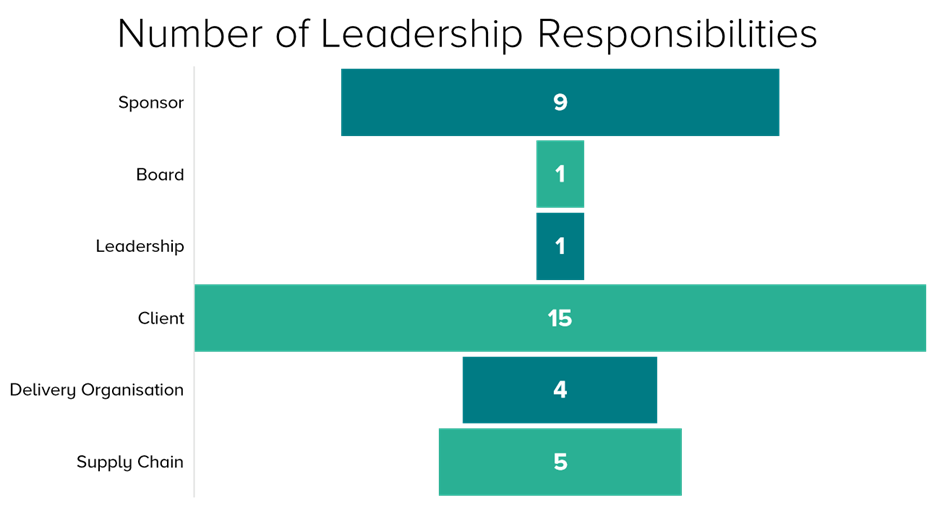

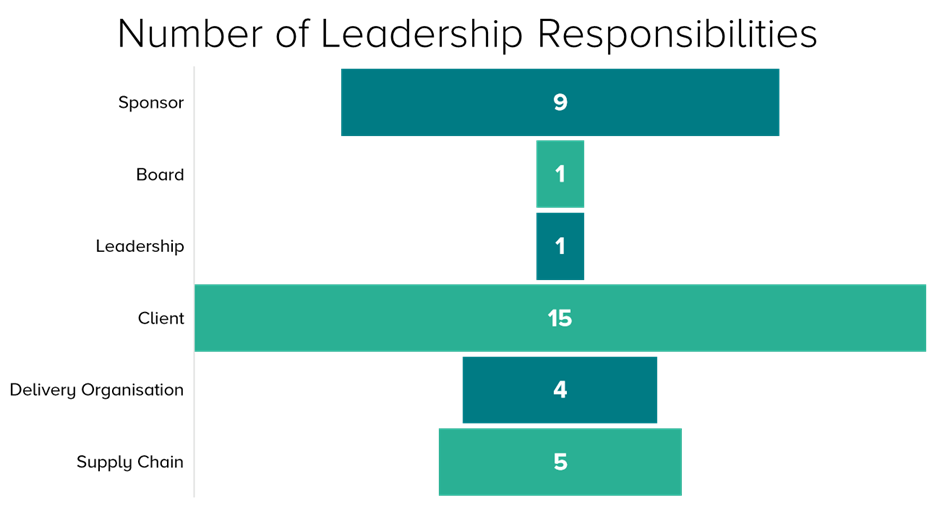

4) Clients were assigned the most leadership responsibilities in a project or programme, highlighting limited leadership from the supply chain. However, there were some responsibilities were across multiple owners such as Funding (Sponsor and Client) and Delivery Model (Client and Delivery Organisation).

The purpose of the workshop was to explore how clienting is done today and whether there needs to be a change in approach, the insights gathered from the workshop strongly allude to the disjointed practices and misconceptions of client responsibilities. There is more that the supply chain can do to support clients achieve their outcomes through effective project and programme leadership.

Emma-Jane’s work developing the concept of the ‘Incomplete Client’ is still ongoing and she would welcome anybody who had anything to share, such as example projects where they have experienced successful clients or have been a successful client themselves. Please reach out to richard.dagama@resolex.com to get in touch.

Although we haven’t worked on this specific part of the HS2 project, we have supported the project in many other areas, and we were thrilled to be invited to the site to see the record-breaking works in action, and learn more about the JV renowned for their culture, collaboration, and ways of working.

Although we haven’t worked on this specific part of the HS2 project, we have supported the project in many other areas, and we were thrilled to be invited to the site to see the record-breaking works in action, and learn more about the JV renowned for their culture, collaboration, and ways of working.