May 8, 2025 | 25 in 25

In 2000, we embarked on a pioneering project with the State of Jersey on the construction of their £15m Alpha Taxiway at Jersey Airport. This initiative marked the first commercial use of a dispute resolution service known as Contracted Mediation – a proactive approach designed to operationalise dispute escalation protocols and enable the swift resolution of issues before they escalated into entrenched disputes.

Midway through the project, a significant disruption occurred in the finish of the taxiway. Under normal circumstances, this could have triggered a prolonged and costly dispute between the airport and the main contractor. However, thanks to the pre-agreed Contracted Mediation process, a panel of independent mediators from ResoLex were rapidly deployed. Over the course of a two-day partnering workshop, they facilitated a deep dive into the problem, working with both parties to seek a constructive path forward.

Crucially, the ResoLex panel approached the issue from a needs-based perspective rather than a rights-based one. Rather than focusing solely on contractual entitlements, they explored what each party needed in order to move forward productively. By mapping out several possible scenarios and outcomes, the panel helped the team realise that continuing a dispute would only divert valuable time and resources. Instead, both parties agreed to prioritise resolution and recommit to the successful delivery of the project.

Following the intervention, both the client and contractor reported that the process had been transformational. They described a sense of relief, a renewed focus on shared goals, and a shift in project culture – resulting in what we would now term a ‘collaborative relationship’. The project team realigned around the question: What does each party need to be successful, and how can we support that?

As a result, the Alpha Taxiway project was completed on time and under budget, despite the challenges encountered mid-project.

Key Takeaway

This experience demonstrated that performance improvement through collaboration requires more than good intentions – it depends on creating a project culture that values needs as well as rights. Contracted Mediation proved to be an effective tool in fostering that culture, turning a potentially confrontational situation into a collaborative success story.

We were gobsmacked and amazed at how quickly and simply ResoLex helped us all reach a satisfactory agreement. – Client representative

Mar 18, 2025 | News and insight

Projects, by their nature, are technical and commercial enterprises. However, what often makes or breaks a project is not a technical issue or even a commercial or cost one – but whether the relationships built can support and drive delivery.

It is easy to overlook the importance of these relationships as projects are driven to deliver quick wins or short-term gains such as “getting a shovel in the ground”. But focusing on these immediate wants risks undermining the long-term needs for our success, including the trust and collaboration that keeps things moving forward, particularly in modern mega- or even giga-projects where delivery is no longer a simple client/contractor relationship but a web of interconnected delivery partners and organisations.

Relationships between these organisations are what drive your delivery – but they are often not considered or worked upon in any meaningful way. At best, we might begin to think about interpersonal relationships, but what about interorganisational? After all, each component partner likely has their own ways of working, their own values, and their own ideas of what success looks like

We see the evidence of this lack of consideration everywhere. How many times have you encountered an organisation – client or otherwise – that is always in a ‘state of emergency’? Where every ask has to be answered right now? Perhaps a few times their partners will go along with it (if they have a good relationship), but sooner or later someone will say “no” – and then where does that leave the asker?

Even within a traditional client/contractor relationship, the client may be constantly demanding that their contractor push costs down, or deliver faster, or deliver more, focusing on the client’s immediate ‘wants’ – but if this results in the contractor failing, both sides lose – the client has a failed project, and the contractor may be facing dire consequences, including insolvency.

Further, in complex modern project environments organisations will often be interacting outside of this transactional “I tell, you do” relationship, and so cannot even fall back on the (as mentioned, potentially unsustainable) “well the contract says you have to”.

So, if relationships are that important to project success, what can we do about them?

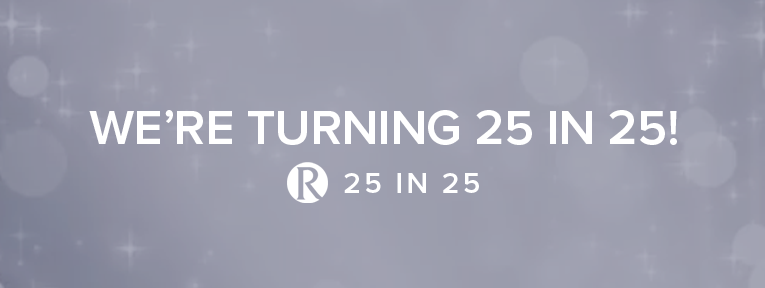

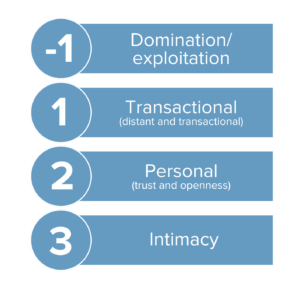

For interpersonal relationships, Schein & Schein set out a model with four ‘levels’:

Can we also apply these to the relationships between organisations? And what would that look like?

- Level -1 would consist of an exploitative relationship where one organisation is totally dominant of another, free to use and abuse them without accountability

- At Level 1, we would have the traditional transactional relationship – client/contractor, where one party holds all the power, and will only ever be thinking about their own needs – or more likely, their own wants, at any given time.

- Level 2 places parties in a position of openness – which enables a deeper understanding of other parties’ needs, as well as your own. Because only through understanding the needs of those you are relying upon to deliver, can you fully understand what yours are, and begin to evaluate your wants in terms of those needs.

- Level 3 would represent a level of intimacy between organisations which is likely unnecessary to most delivery environments. It may have a place in certain places where an acutely high level of trust and dependence is required, but otherwise, it applies far more to our personal relationships than our professional ones. It may even be detrimental, where clients favour one organisation to the exclusion of others, or two partners are co-dependent for any decision-making!

As with interpersonal relationships, Level 2 is the ‘sweet spot’ for delivery. Both parties recognize that achieving long-term goals means building mutual trust and aligning on shared objectives. Instead of viewing interactions merely as exchanges of services for payments, Level 2 encourages us to see our partners as collaborators whose success is intertwined with our own. This shift from a wants-based approach – built upon a system of ‘knowing your rights’, where contracts and legal obligations dominate – to a needs-based mindset opens the door for genuine problem-solving.

And, if those technical or commercial issues do raise their heads – you can proactively resolve or mediate them rather than resorting to costly disputes, where ultimately nobody’s needs will be met!

Tom Chick is a senior consultant at ResoLex specialising in building effective working environments in major projects. If you want to learn more about how to get the most out of your professional relationships, contact Tom here or connect with him on LinkedIn.

Mar 11, 2025 | News and insight

From the moment a major project is announced, there is a societal, political and organisational pressure to deliver the intended benefits as quickly as possible. This pressure creates a culture that champions technical delivery above all else, pushing teams towards the ‘build’ stage of the project life cycle before they are ready. As a result, many of the key elements critical to the project’s success are neglected or poorly planned, and come back to bite us later.

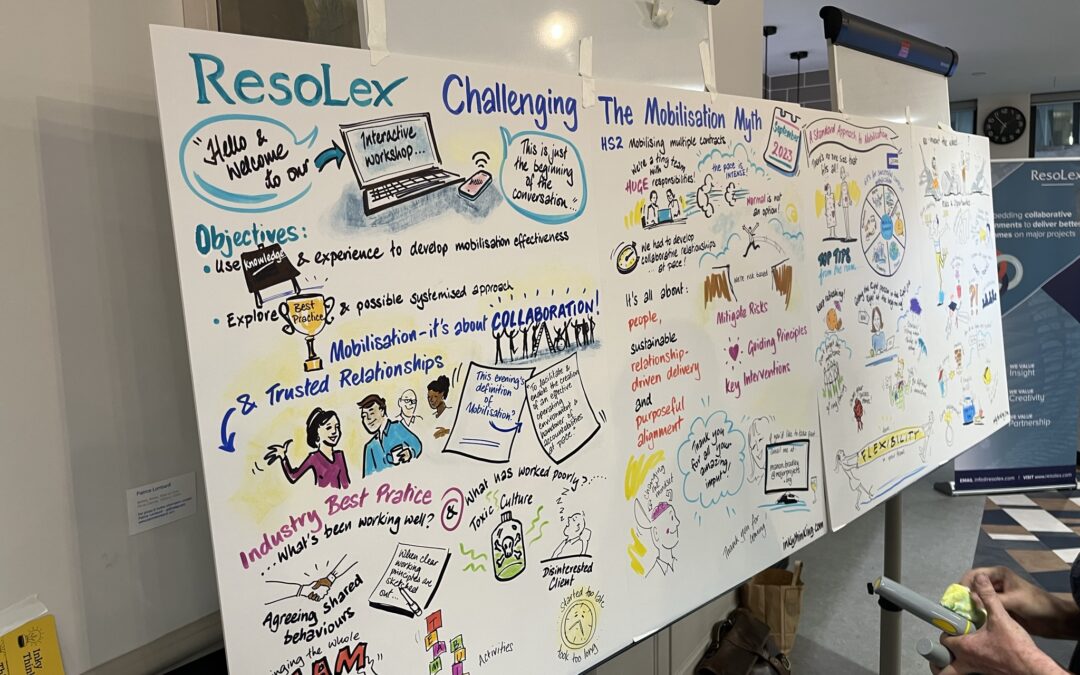

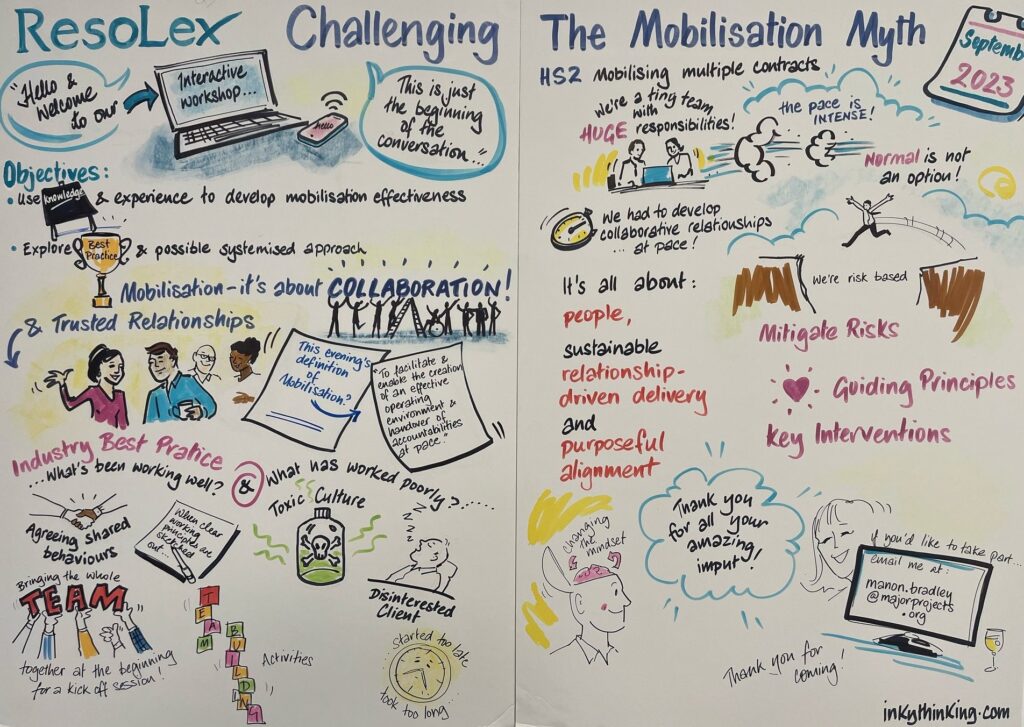

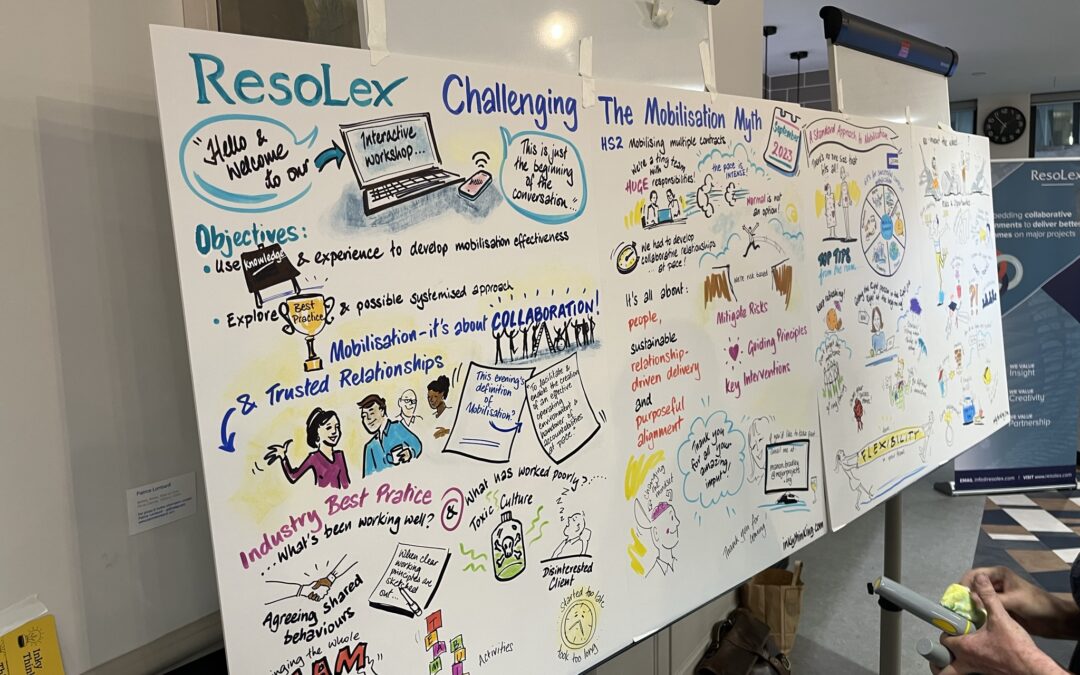

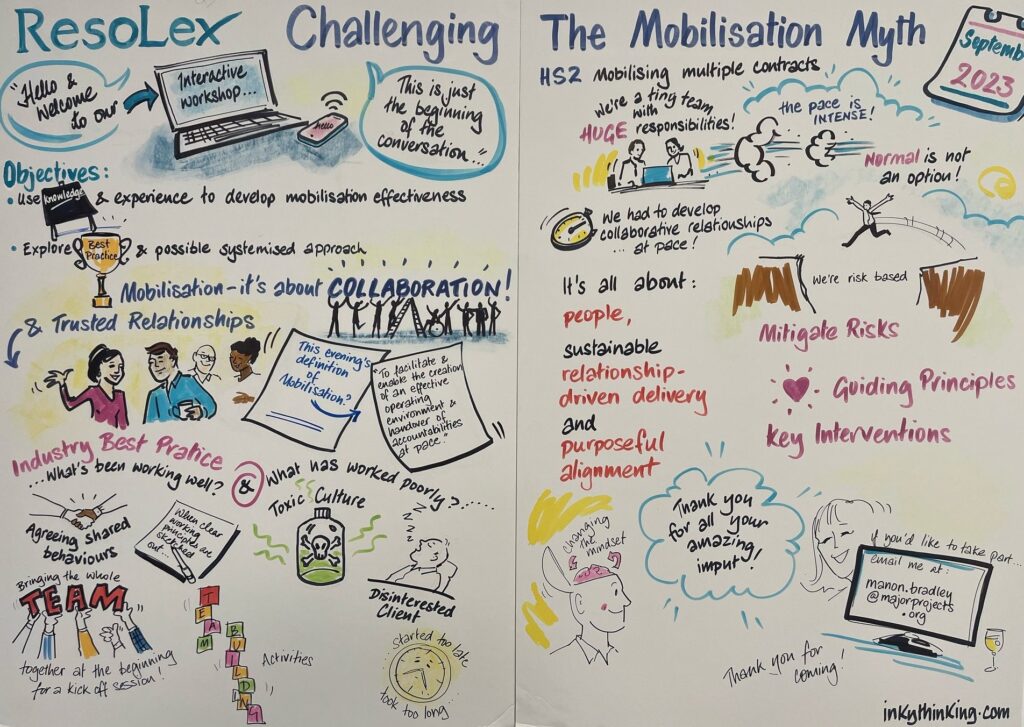

Back in September 2023, we teamed up with the Major Projects Association to host a workshop called ‘Challenging the Mobilisation Myth: Driving performance through effective Contract Mobilisation’.

We brought together experienced project professionals from government and industry, including representatives from Costain, HS2, DEFRA, Jacobs, HKA, GBR, and East West Rail, to discuss the common issues affecting mobilisation. Since then, we’ve been busy in the background working with the MPA and some attendees of the workshop to develop our latest perspectives paper, ‘Mind the Mobilisation Gap: Why we’re still getting mobilisation wrong on major projects, and how we can do better’.

Co-authored by Lisa Martello and Tony Llewellyn of ResoLex, the Perspectives Paper brings together practical thoughts, observations and recommendations on how to plan and deliver project mobilisation successfully. Its objective is to:

- support project organisations to consider and embed mobilisation as a critical stage in the programme

- provide guidance on the time, attention and resources it needs and deserves in order to be successful.

Read the full report here.

About the authors:

A project manager by trade, Lisa Martello has more than 15 years’ experience building and leading diverse, collaborative, and inclusive teams on major infrastructure projects in the UK and Australia. As a Director at ResoLex, Lisa specialises in strengthening the social, behavioural, and cultural components crucial to achieving desired outcomes within major project environments.

A project manager by trade, Lisa Martello has more than 15 years’ experience building and leading diverse, collaborative, and inclusive teams on major infrastructure projects in the UK and Australia. As a Director at ResoLex, Lisa specialises in strengthening the social, behavioural, and cultural components crucial to achieving desired outcomes within major project environments.

Originally training as a surveyor, Tony Llewellyn has spent over 30 years working on major projects, and is now an Author, Coach, Lecturer, and Thought Leader on the topics of performance improvement, interpersonal dynamics and the effectiveness of project teams. As a Director at ResoLex, Tony helps teams and leaders improve their outcomes by helping them to build trust, communication and collaboration.

Originally training as a surveyor, Tony Llewellyn has spent over 30 years working on major projects, and is now an Author, Coach, Lecturer, and Thought Leader on the topics of performance improvement, interpersonal dynamics and the effectiveness of project teams. As a Director at ResoLex, Tony helps teams and leaders improve their outcomes by helping them to build trust, communication and collaboration.

Feb 26, 2025 | 25 in 25, News and insight

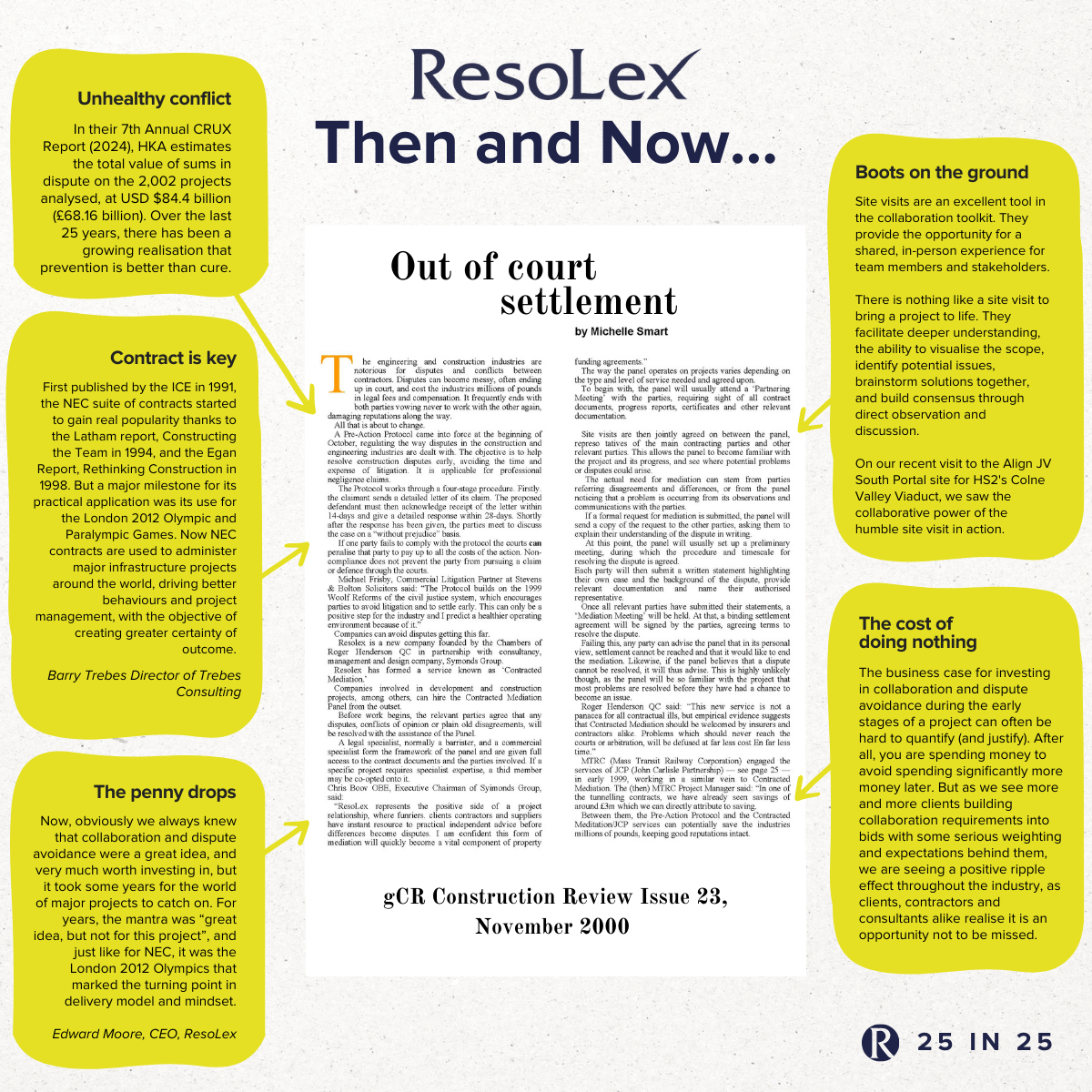

To celebrate our 25th birthday, we went fishing about in the ResoLex archives, and look at what we found! This is the very first article written about ResoLex back in the year 2000. It talks about the messy and costly disputes and conflicts that plague the engineering and construction industries, and introduces ResoLex as a positive and proactive partner that can help prevent differences from becoming disputes.

25 years on, and that remains our mission, and the facts and figures tell us it is more important than ever. Have a read through the article and our modern day insights, and tell us about the change you’ve seen over the years.

Click here to open the original article from 2000.

Jan 31, 2025 | 25 in 25

2025 is an important year for ResoLex as it marks our quarter of a century.

ResoLex was founded in the year 2000 with what we now realise was a very forward-thinking approach to supporting project success.

The idea that purely transactional behaviour on a project does not lead to the most successful outcomes was, and remains, at the heart of what Resolex stands for. We have been pushing for the creation of collaborative delivery environments on complex projects for 25 years, but when we began, we were, if not lone voices, part of a very small group indeed.

Thankfully, since then there has been a movement towards more collaborative delivery and commercial models in complex projects, and we are proud to have played a part in driving this change. 🤝

We will be celebrating our 25th birthday in a multitude of ways this year, so watch this space! 💫

A project manager by trade, Lisa Martello has more than 15 years’ experience building and leading diverse, collaborative, and inclusive teams on major infrastructure projects in the UK and Australia. As a Director at ResoLex, Lisa specialises in strengthening the social, behavioural, and cultural components crucial to achieving desired outcomes within major project environments.

A project manager by trade, Lisa Martello has more than 15 years’ experience building and leading diverse, collaborative, and inclusive teams on major infrastructure projects in the UK and Australia. As a Director at ResoLex, Lisa specialises in strengthening the social, behavioural, and cultural components crucial to achieving desired outcomes within major project environments. Originally training as a surveyor, Tony Llewellyn has spent over 30 years working on major projects, and is now an Author, Coach, Lecturer, and Thought Leader on the topics of performance improvement, interpersonal dynamics and the effectiveness of project teams. As a Director at ResoLex, Tony helps teams and leaders improve their outcomes by helping them to build trust, communication and collaboration.

Originally training as a surveyor, Tony Llewellyn has spent over 30 years working on major projects, and is now an Author, Coach, Lecturer, and Thought Leader on the topics of performance improvement, interpersonal dynamics and the effectiveness of project teams. As a Director at ResoLex, Tony helps teams and leaders improve their outcomes by helping them to build trust, communication and collaboration.