Apr 26, 2018 | Events, Roundtables

Barry TrebesFRICS, FAPM, FInstCES

Barry is a Chartered Surveyor, initiator of the first web-based NEC management system in 1990. He co-authored NEC Manuals; “Managing Reality”, NEC3 Role of the Supervisor and NEC3 Role of Project Manager and the BSi published document, Project Management in the construction industry.

This month’s round table was designed to encourage an exploration of the use of the NEC4 contract as a tool for collaboration. Any summary of any discussion on construction contracts is fraught with danger in that the commentator can either over-elaborate or alternatively completely miss a critical point. We offer the following as an attempt to find the right balance of the evening’s discourse.

The aim of the NEC suite is that of taking a contract off the shelf and add the detail. Within the off the shelf contract, the promotion of collaborative behaviour is a given. The overriding message from NEC4 is that contracts work when people understand the risk within the contract. Drafted for use anytime and anywhere with a mix of options designed to be project-specific NEC4 is evolution not revolution. The overriding principle is one of agreeing change as the project proceeds to a timescale to give certainty of outcome. The contract form is demanding in terms of “doing things”, particularly in the following areas:

• Better management practice

• Good risk management processes

• Collaboration

• Alliancing

• Good communications

• Change management

Of key importance are the ‘early warnings’ for risk management and change management with a contract expectation that to get the best out of its use there will be an investment in supporting resources both in terms of people and systems. Early warnings are important in focussing on communications so that early warnings are “scouting ahead looking for risks”. The expectation is that the early warnings register will interface as an EWS tool for the early warning of risks to be fed into the risk register. The prevailing ethos of NEC4 is one of looking ahead and forecasting rather than forensic analysis. This is relevant in the areas of BIM and ECI with options reflecting specific project circumstances.

The overriding operating principle of the use of Z clauses is “What is the mischief you are trying to deal with?” There is an attempt to pre-empt the misuse of Z clauses where project specific “boilerplate” drafting attempts to change the contract into something it is not.

There is a refinement of processes with the intention of interfacing with project management systems particularly around early warnings systems (EWS), programming, contractor’s proposals, and proposed instructions.

Encouraging collaborative behaviour

NEC4 Alliance Contract, intended to unite teams, launches at the NEC Conference on 20th June. Again, the key question is “Can any contract force you to collaborate?” While the contract is important, collaboration comes back to better management.

There are also improvements around the status and use of contractor’s proposals and throughout the contract clarifications and simplifications around the schedule of cost components.

NEC4 also introduces the consequence of inaction through sanctions, be they from the project manager or the contractor. Changing circumstances need supporting by risk EWS, programme forecasting and continuous final assessments.

Risk allocation is vitally important in drafting contracts. There needs to be a better fundamental alignment of risk allocation under all contract forms. In putting together and delivering contracts use of better risk identification is needed with more open allocation of risk between client risk and contractor risk. In NEC4 project specific attention needs to focus around clauses 80.1 client liabilities and 81.1 contractor liabilities. Early warnings should find opportunities to mitigate risk, particularly relating to supporting BIM, dispute negotiation and dispute avoidance which all impact on financial agreement.

There is a view in some quarters that without the right working processes and systems, too much collaboration activity exhausts employees and saps cooperation. Questions are now asked around whether there is collaboration overload. The distribution of collaborative work is often lopsided. Effective collaboration needs rewarding. One solution is to develop a series of KPIs that will stimulate collaborative behaviours on a group basis.

So, whilst NEC is good on processes, there is a question as to whether any form of contract can shape human behaviour other than to put constraints that lead to transactional project culture. Questions posed in the room included:

•How this might change?

•What is there that is complimentary to risk and collaboration?

•What is the wisdom to get collaboration to work?

The emerging theme was that investment is key both in terms of resources in the form of systems to support the contract and coaching and mentoring to encourage parties to work together. Collaborative intelligence presupposes a willingness to collaborate and share and knowing how to share. This means understanding team dynamics and using the right tools and the right technology to support aspirations. This in turn means proper communication and using the right supporting processes.

People tend to use the contract form they know. Organisations have invested a great deal in their preferred contract forms and this gives familiarity. NEC4 is gaining influence and take up. However the move from NEC3

will take time because of the previous worthwhile investment in the NEC3 form. There are no concerns as to take up and it is envisaged over time that evolution will move from NEC4 to NEC5. Ultimately theclient decides on the form of contract. Any effective collaborative contract needs an investment in people and systems to support its use.

The bottom line was that irrespective of the form of contract chosen, sharing information and communicating give better outcomes.

Tony Llewellyn, April 2018

Mar 1, 2018 | Events, Roundtables

How do we (finally) turn words into action?

Don Ward, Chief Executive of Constructing Excellence

Don began the session with a statement that the mission, not just of CE but also the people in the room should be to “positively disrupt the industry delivery process to transform performance.” He pointed to the accumulating evidence gathered over the past 20 years of projects where a collaborative approach between the client contractor and supply chain have produced more successful outcome than would have been achieved through a typical transactional approach.

Apart from the high profile ‘mega projects’ such as BP Andrew, Heathrow T5, London 2012, Crossrail and Thames Tideway, Constructing Excellence have collected data from over 500 projects from all sectors, regions and sizes. This data shows that projects can be delivered 10 –20% cheaper and produce better client outcomes using some form of collaborative arrangements such as partnering, alliances or other mechanisms, where the client and supply chain team work as an integrated unit.

So if the evidence there to prove that a collaborative approach works, the obvious question is “why don’t we do it?”

Don showed a slide setting and some of the barriers which included:

• Lack of crisis to stimulate change at an industry-wide level.

• Low awareness of the potential benefits, particularly in key advisors such as quantity surveyors and project managers.

• Lack of a standardized approach by clients.

• No continuity of pipeline.

• Poor leadership and lack of understanding of collaborative team coaching.

• Poor training and development.

• Focus on initial cost rather than whole life value.

• Obsession with the lowest price tendering.

•Failure to keep project teams together.

• Strong vested interests in the status quo

There was a lively debate in the room as different members of the audience voiced their own views on the factors which discouraged collaborative engagement.

Projects are complex

An interesting point was made that the true design process was rarely achieved solely by the architect or engineer. On complex projects, the evolution of the final design also involves the contractor, the specialist sub-contractors and others. Lowest price tendering tends to ignore this important reality.

Another guest commented that simply changing the focus within a client organization from outputs to outcomes nudged their project teams to stop looking solely at their own workload and instead think about their contribution to the whole.

Don identified six critical success factors for collaborative working:

• Early supply chain involvement

• Selection by value, not lowest tender

• Common processes and tools

• Measurement of performance

• Long-term relationships

• Aligned commercial arrangements

These factors provide any practitioner with a framework to build a collaborative relationship.

The session closed with a three-stage formula for transformation:

1. Change the Delivery model

2. Change the Procurement model

3. Change the business model

I would highly recommend that you have a look at the slide deck Don used, as there is some very useful information. Don is an accomplished presenter and he kept us all fully engaged for 90 minutes. Reflecting on the session, I have a clearer perspective on the progress made by the ‘collaboration’ movement and am looking to incorporate some of Don’s thoughts and ideas into ResoLex’s working practices.

Tony Llewellyn, March 2018

Feb 1, 2018 | Events, Roundtables

A Case Study from Surrey Highways and Kier Services

The session was opened by David Mosey who provided a short explanation of the FAC1 Framework agreement. For those not yet familiar with FAC1, it provides a framework for organisations to enter into an agreement that will enable and support the award of a number of contracts whilst not itself being a project contract. The agreement anticipates a situation where a client wishes to set up a longer-term partnership or alliance and needs an overarching document that covers:

- Joint planning and risk management

- Improved consistent working practices

- Encourages learning to be passed from project to project

- Achieves improved value through collaborative working

David used an example from a roads maintenance agreement, involving Surrey County Council, Kier Services and a number of specialist subcontractors. The agreement used an early prototype of FAC1 to help Surrey Council generate savings of roughly 15% from the original tendered contract as well as a number of additional benefits.

The FAC1 agreement is only 18 months old but has already been picked up by a range of public and private organisations who are investing in development programmes.

Nigel Owers then explained the background to its new Alliance program. Kier had originally won a tender for a 6 year highways maintenance contract in 2011, which gave Surrey the option to extend by an additional four years. Having successfully delivered the initial term of the contract, the council agreed with Kier to extend the contract to 2021. The extended agreement is intended to deliver continue additional value and innovation through the supply chain through revised and collaborative arrangements. The strategic goals of the Alliance are:

- Increased collaboration between SCC, Kier and the supply chain

- Achieve the objectives of the Surrey Business Plan

- Find a further 2.5% saving

- Develop a sustainable supply chain through to 2021.

Nigel ran through the re-procurement process and explained how the Alliance agreement was implemented. A useful illustration is a summary of what the Alliance members have agreed to do:

- Hold Core Group meetings;

- Adopt and participate in early contractor involvement (“ECI”)

- Share and/or improve working practices for the benefit of Surrey and the Term Programme

- Attend other framework review meetings as required in order to achieve improved value

- Implement social value proposals

Measurement and feedback are important elements. For example, the agreement sets out four success measures:

- Performance Review

- Social Value

- ECI

- Alliance participation

Nigel closed by acknowledging that the Alliance was still in a learning phase and that the parties were each still getting used to the new arrangement. It was interesting to note that those individuals who were part of the previous alliance programme were apparently comfortable with the open dialogue that featured in the first Alliance meeting. Those who were new to the format were much less certain as to how to make the adjustment from a transactional set of behaviours to the collaborative mindset required as part of this alliance.

Keith Coleman then presented the Alliance process from his perspective. His role is Head of Contracts and Supply Management at Orbis, an organisation formed to provide procurement services to Brighton and Hove, East Sussex and Surrey Councils. Keith explained the drivers created by the huge funding gap that all local government bodies need to close. They are therefore continuing to explore mechanisms that will enable them to gain additional value by setting up collaborative arrangements with key suppliers. There is consequently is a shift, both within local and central government, away from short term lowest price bidding.

Keith talked about the progression of different relationships to deliver better value from a procurement perspective. These range from category management and strategic sourcing through to supplier relationship management. For many procurement teams the Alliancing framework is a significant stretch requiring a new mindset as well as new processes and procedures. He nevertheless envisaged an additional stage where major buyers such as local government might take the Alliancing process to encompass entire markets.

For example, Surrey currently deals with 400 separate care home providers. He asked the room whether it might be conceivable that an Alliance framework could be used to find greater value from such a dispersed network? Keith did not suggest any answers but left the room with a clear sense that given the right mindset and the appropriate toolkit, much more was possible.

Jan 17, 2018 | Events, Roundtables

Speakers:

- Nicola Walters | Assistant Director, Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy

- Alan Kirk | Head of Commercial – Capital Delivery (Systems), TfL

- Rudy Klein | Chief Executive, Specialist Engineering Contractors Group

- Richard Bayfield | Consultant and Commercial Risk Director, Temple Group

The theme of this month’s discussion was around the consultations currently taking place on:

- The changes to Part 2 of the housing, grants and regeneration act.

- The Construction payments mechanism.

Nicola opened the session, explaining the purpose of the housing review is to understand the impact of the 2011 legislation and see if it needs tweaking. It is not currently envisaged that there will be any major changes.

The review of the payments mechanism is to look at the policy on retentions and understand the industry views on the extent to which monies retained by clients, and contractors should be protected to avoid misuse. The review will also look into the adjudication process to understand whether the system works for organisations further down the supply chain.

The speakers then picked up the topic to talk about the adjudication issue as it affects large clients. There was consensus that the system is not really working as originally intended, largely because:

- Cash flow is still a big problem despite the introduction of adjudication

- Adjudication itself has become more expensive than originally anticipated.

Richard highlighted the problem of drafting legislation which intrinsically requires a “one size fits all” approach. He used an example from a recent adjudication where the lack of legal/contractual sophistication was shown by correspondence supporting a “pay when paid” approach. He cited the large bandwidth within the industry from the “jobbing builder” work to the mega infrastructure projects.

Alan felt that it was important to see greater input to projects from the T2 and T3 subcontractors since they have the potential to add value if properly engaged.

It was noted that a number of public sector clients are unhappy with inconsistency between the commercial arrangements agreed with the T1 Contractors, and those further down the supply chain. This was a significant concern for them, as they were increasingly of the view that the value and innovation they were seeking would only likely to come from the subcontracting firms who delivered the works. Rudi was unhappy with the current contracting model of the major T1 contractors becoming cash management businesses that paid little attention to the productivity gains being sought.

The case was made for a simpler system for payment claims, as had recently been put in place in Ireland. More safeguards are also needed to prevent clients and main contractors introducing workaround clauses that essentially void the effect of trying to eliminate ‘pay when paid’ practices. Some other recommendations were:

- That the adjudicators should be able to decide their own jurisdiction.

- The scheme procedure should be specifically mandated

- There should be no extension past 42 days

- The industry should work towards an efficient ‘on-line’ approach.

Other thoughts

As usual with the Round Table events, the discussion that followed the short presentations was varied and insightful. Some of the noteworthy points are set out below.

The collapse of Carillion was felt to be highly unfortunate for many in the construction industry but was of sufficient scale that it was likely to provoke a call for significant change in the industry. The clear message to the government was that pushing risk down into the private sector had its limitations and should be re-assessed.

Similarly, the financial model of competing for work at extremely low margins was unlikely to ever produce the productivity gains that the agencies delivering major programs of infrastructure work were likely to achieve.

It was felt that the collaboration agenda in too many firms were focused on technical issues and tended to ignore the social/behavioural aspects that were fundamental to achieving a step change in productivity. (This was obviously well received by the ResoLex team who have been promoting this view for a while.)

Rudi summed up the evening with three areas for future focus for improvements across the construction industry. His three ‘P’s are;

1. Procurement – Look more closely at innovative procurement processes such as IPI. (see the notes from the November round table)

2. Payments. Set up project bank accounts for all major projects and look after the interests of all parties in the supply chain.

3. Professionalism. Introduce higher standards of behaviour and business practice.

Nov 21, 2017 | Events, Roundtables

Speaker: Kevin Thomas, Director of IPInitiatives

The session opened with Kevin making the statement that the UK construction industry is capable of achieving great things, but tends to be successful despite the process, rather than because of it. change gets more expensive as the design of the project progresses from design to delivery, often because there is a lack of ownership of the overall outcome. The IPI model recognises combines the two processes so that the client designers and the delivery supply chain all combine to work as a single team under an ‘alliance’ agreement.

The key features of the arrangement include

- Common selection process (OJEU) based on ability to achieve.

- New Alliance Contract creates a virtual business ‐ a Board of partners with ‘skin in the game’.

- The whole team optimise performance deciding who does what, when and how.

- Open book – pay for people and buy things separately – through a Project Bank Account.

- Work top-down from a benchmarked investment target to meet the needs.

- Supply chain is involved in all design decisions.

- Savings are achieved by stripping out processes, products and procedural waste & inefficiency.

- The team identify opportunities and risks ‐ allocating them to the party best suited.

One of the key features of the arrangement is that all of the usual insurances taken out by the different parties to a construction contract are wrapped together, to provide the client with protection against a cost overrun.

New mindset required

The process requires a significant shift in mindset by all of the participants. There are many different features to the IPI process, but one of the biggest changes is that there is no one to blame under a contract, because everyone is tied together. The process works through the following steps:

Step 1 – Establish the Need. The problem to be solved and the funding level anticipated

Step 2 ‐ Form an Advisory Team. Establish the strategic brief & success criteria, validate the investment target and select the team

Step 3 ‐ Establish the Alliance. Client and key partners bound together through an alliance contract and gain/pain share incentives who confirm the functional requirements, propose the solution and confirm the target cost

Step 4 ‐ Approval to Implement. Client & underwriter approval to develop and deliver the solution and incept the IPI policy to cover the agreed target cost

Step 5 – Implementation. Open book collaborative design, development and delivery

Step 6 – Transition to Defects Liability. Completion and proving, 12 months of soft landings and seasonal commissioning and 12 years of defect liability

Case Study – Dudley Advance II.

The IPI model has had a long gestation period, being first conceived in 2003. It has finally been tested on a live project for Dudley College. This is a higher education facility comprising five floors of lab/teaching space and a large open hanger-like space for large-scale projects. The building is stacked with innovation, and built to a high finish.

The project began in 2014 and was delivered to the client on the program for the start of the educational term and within the original cost parameters. Given the challenges that the team faced over the delivery period, it is likely that the building would have faced significant delays and would have incurred significant cost overruns, had it been built using traditional design and procurement methods.

Kevin provided the audience with a frank summary of the learning from the project. Some of the things they expected to happen include:

- A true no-blame culture would emerge

- A “best for project” focus would be adopted for solution development and problem-solving

- Supply Chain would engage, lending expertise so design happened only once

- The team would run the project on Opportunities and Risks

- The Alliance Board would function as a business board

- BIM would create better efficiency, give asset management solutions

- New processes and procedures would be created

- Behaviours would change

Some of the things that were unexpected included:

- Working within the investment target is not a core skill for many people in the industry.

- The level of facilitation, coaching and mentoring was much higher than anticipated.

- It initially took a lot of effort to get people to take leadership.

- How much support some businesses would need to adopt BIM

- Impact of adopting BIM guidance

- Limitations of the ‘normal’ programming processes

- Cost of and time to achieve policy inception

- Difficulty integrating design, delivery & commissioning activities

- The extra benefits of 4D

Summary

Having been aware for some time that the IPI pilot was running, the ResoLex community were excited to see how it would turn out. The room was therefore delighted to hear of the IPInitiatives team’s experiences, and many were keen to see how the process might be used on their future projects. Kevin was keen to point out that the process is still in its early stages, and whilst there is another pilot currently underway, there is still a long way to go before the process becomes a mainstream alternative to the traditional procurement route.

One of my main takeaways from the evening was Kevin’s observation that once the collaborative mindset took hold, the energy and desire within the team to deliver was a joy to work with. Many words are written and spoken about the need for more collaboration in the construction industry. Kevin and his fellow directors have shown us how it can actually work in practice!

Oct 24, 2017 | Events, Roundtables

Speaker: David Hawkins, Operations Director and Knowledge Architect of ICW (Institute for Collaborative Working)

David began his presentation by comparing the contrasting perceptions of collaboration of synchronized swimming with sharks at one end and a team hug at the other. Neither is a true picture of what collaboration really means.

He explained that as business is shifting, old adversarial practices are proving inadequate to meet the challenges of organisations seeking to compete and survive in the 21st century.

In construction, whilst individuals often collaborate, organisations do not. There is too much reliance on informal relationships which disappear when the people move on. The aim of the standard is to establish formal structures so that the relationships are maintained irrespective of the people involved. The Standard gives companies a language and a platform upon which to develop a more effective way of working.

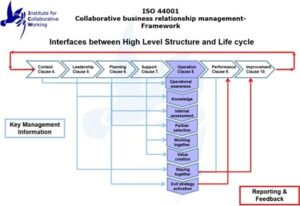

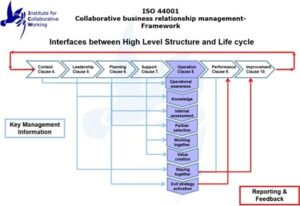

As can be seen from the slide deck, the standard is designed around a number of stages, each one asking the parties to think and plan how they will work together. The structure of the model is illustrated below.

Some of the useful insights from the presentation were as follows:

- That most organisations are inefficient and waste a great deal of inefficient

- There is and assumption that people will use their common sense – Voltaire commented back in 1694, ‘common sense is not so common’.

- Constructive conflict can drive innovation. This occurs when collaborative relationships are really working effectively.

- Universities are still teaching a 40 year old command and control model ill suited to the modern complex economy. A survey of project managers highlighted that the biggest challenges are with relationships. One of the real challenges is the lack of skills to implement the collaborative process.

- The Standard is not a set of proformas. The danger with such an approach that is the organizations mechanism not an external consultant.

- Risk – Observation that banks and insurance organisations are going to be much more concerned about relationships risk in the futures as they begin to understand the value created by effective partnerships.

- Contracts – tend to be written in anticipation of failure rather than seeking to drive the conditions for success. David expressed the view that NEC4 has missed the opportunity to push the industry to push the boundaries and encourage the client and the contractor to approach public projects in a different way.

David concluded the session by reiterating the point that the key to success is the belief of the senior leadership. He emphasized the point that simply having the certificate on the wall is largely a waste of energy. The objective must be to use the Standard to build a better business.