May 30, 2025 | 25 in 25, News and insight

As we celebrate 25 incredible years of ResoLex, we’re shining a spotlight on some of people who make it all possible — our Associates.

We asked a few of them to share why they choose to be part of the ResoLex team, and their reflections have been nothing short of inspiring. Here’s what Russell Poynter-Brown had to say:

“I was delighted when Ed and Tony asked if I’d come and work with them on a high-profile, complex and multi-stakeholder programme, especially as a key workstream centres on collaborative working.

In all honesty, I’d almost given up on the construction and infrastructure sectors, as it is so rare to find clients, consultants and other advisers who fundamentally understand what it takes to work in a truly collaborative environment.

ResoLex is refreshingly different. It uses its 25 years of expertise and insights to constructively challenge clients and then work with them to think laterally, suspend judgement, and then co-create programme-specific practicable, long-term value-added solutions, with measurable programmatic benefits.

The ResoLex team is a constant source of creative ideas and solutions. I‘ve never felt freer to work in a psychologically safe environment, where I can test my thoughts or ask for comments and opinions without feeling that I’m being judged or fearing that the Team already has a ‘stock’ answer that I’d be forced to adopt.

Highly complex programmes invariably have their challenges which can often adversely affect working relationships. However, ResoLex has a fundamental understanding of how people work in teams, in particular the interaction between people, processes and the environment within which team personnel work. I’ve been fortunate to be able to tap into this knowledge bank and adapt several ‘in-house ‘ models for our programme client’s benefit, enhancing its ability to work in a more collaborative way.”

Stay tuned on LinkedIn throughout our birthday celebrations as we continue to showcase some of the voices behind ResoLex — the people driving impact and making a real difference every day.

Apr 26, 2024 | Events, Roundtables

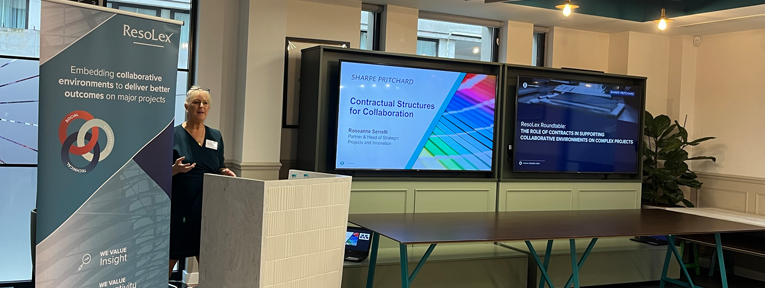

On the 23rd of April, we welcomed Roseanne Serrelli, Partner at Sharpe Pritchard for a discussion on how contracts can be used to help embed collaborative behaviours on complex projects.

The session was opened by our Chief Executive, Edward Moore, who gave the attendees an overview of the evening and an introduction to the topic.

Ros began her presentation by explaining that the terms used in these ‘collaborative contracts’, e.g. alliances, enterprises, partnerships – have no specific legal definition. Any individual party involved with the contract is likely to interpret these terms differently. The key when looking to develop a contract which supports a collaborative endeavour is to focus on attention on the purpose of the relationship, rather than the term used. This approach has the benefit of shifting the focus away from risk transfer and instead puts the focus on risk avoidance and resolution.

The level of collaboration built into a contract can therefore be bespoke based upon the need, rather than starting with a pre-populated document. Options exist along on a spectrum from a light-touch arrangement to full alliances with shared legal risk, reward and finances. When developing a contract, it is worth thinking of the options as a menu from which the appropriate provisions can be selected based upon what the client intends to achieve.

Ros talked through several examples of different collaboration systems in existence, some of which have been discussed at previous ResoLex roundtables:

- Project 13 – not a contract itself, but an ecosystem and ethos for delivery that focuses on achieving outcomes rather than on the inputs.

- NEC Alliance – a single contract to which all are parties, including the client. This often works better on an ongoing programme with repeatable work, where the goal is to incentivise shared responsibility. This is more difficult on single projects where there may be more single points of failure that cannot be shared easily between participants.

- X12 – An option within NEC contracts that seeks to support multi-party collaboration, including containing a common set of objectives for all parties.

- FAC1 – An overarching framework that sits above individual contracts and contains items that need to be supported by those contracts, such as early warning systems.

Regardless of the form of the contract, there were some key takeaways about what is needed to ensure collaboration can be effectively supported:

- A defined governance structure with clear roles and accountabilities (often in a RACI matrix) – make it straightforward for people to understand who is doing what in the contract environment (and be clear that accountability is not the same as liability!)

- A clear decision-making process – the process may evolve over the lifetime of a project or differ in different parts of a programme, but it needs to be set out clearly and communicated to everyone involved.

- Set up Core Groups and Boards – these do not need to be over-engineered. They should have clearly defined objectives and discussion/decision points.

These structures provide a foundation for a successful collaboration. Having a contract that does not enable the environment you want will undermine your project from the start, though equally, having the perfect contract is meaningless if people do not engage in the right ways of working.

The contract underpins the practical side of collaboration; namely regarding people and their behaviours. When setting up for success, the behaviour of the joint team will be a key factor in how the benefits of these structures and processes are maximised in the project or programme environment.

The development of appropriate ways of working should consider some key questions, including but not limited to:

- Will the arrangement require co-location or jointly employed resources?

- What is the communications strategy? Will there be joint messaging from all parties? Will there be common branding and a ‘united front’ when facing the public?

- What are the processes for change or bringing in new people?

- What is the process for sub-contracting? Does the client need to approve any additions?

- How is the project insulated from outside noise (e.g. political pressures) to enable the team to focus on delivering the outcome?

- What do you do when things go wrong? It cannot be assumed, even with the perfect contract and the best people for the job, that there will never be an issue or point of contention between the parties. Provisions should be included in the agreement to enable parties to exit as necessary. Though counterintuitive, Ros shared that her experience is that providing clarity about the exit process provides comfort to the parties and in fact, often encourages parties to stay in contract and work through the challenges.

The session closed with a stimulating discussion on what needs to be done to try to build more collaborative environments in projects and programmes and how contracts can facilitate that, recognising that they are usually the starting point for the relationship. Points were raised in the room on the importance of ‘selling’ the benefits of this approach, particularly to clients when setting up a project and to politicians who may be overseeing major schemes. The conversation was a good reminder of the need to take the time to clearly define the required outputs and outcomes of a scheme before diving in, in order to set up the contract and environment that best facilitates these outcomes.

Nov 21, 2022 | News and insight

20 years ago, ResoLex focused on dispute resolution for teams involved in major projects and complex environments. Over the years, we have developed a deep understanding of how people work together in teams and within the stresses and strains of complex environments – a recipe for behavioural risk! Fast forward to today, and we use that knowledge to help teams strengthen their social competencies, manage behavioural risk and embed a collaborative environment to deliver better outcomes.

Our focus is always on the people: how individuals come together to form a team, the impact of the project environment on relationships and the function of processes and structures to enable people to deliver successfully. So, what do we mean by ‘create more than just a team’? We all strive to create a team that is more than just a workgroup. Our aim is for teams to be effective, but what does that look like?

In major project delivery or any complex environment, an effective team is one that can respond with agility and develop new solutions to the dynamic challenges that the environment brings. A team like this is often made up of people with diverse perspectives, who can safely challenge one another to get to the best outcome. An effective team must have a psychologically safe culture – enabling individuals to feel included and encouraged to contribute their diverse perspectives to the benefit of the project.

One of the early challenges for project leadership is to decide how to bring diverse groups together so they can work effectively, not just on their own element of the project, but critically in the way they support the outputs of other teams with which they must interact and here lies the importance of communication and aligning cultures. Edgar Schien argues* (and we agree!) that for humans to work effectively together, they need to engage based on ‘level two relationships’ – personal, cooperative and trusting relationships where we see others as human beings, acknowledging the whole person and with symmetry in the confidence and trust that each person in that relationship can have in the other (without symmetry, the relationship will remain transactional or will even end). In a ‘level two relationship’, we have a greater level of knowledge of the factors that shape the lives and behaviours of those we work with regularly. When we have a greater degree of understanding, we accept others for who they are as human beings rather than simply identifying them with the job they do. We are consequently more able to build the trust, respect and healthy interactions that are critical to creating psychological safety and laying the foundations for the high-performing team that we desire.

Without this work, project teams are at risk of defaulting to the kinds of behaviours that lead to a hostile working environment, blame culture and workplace bullying, which are not only unpleasant to experience but lead to underperforming, ineffective teams.

This blog was inspired by Anti-Bullying Week, and you might be wondering, what does that have to do with building an effective team?

The Anti-Bullying Alliance (ABA) are the official organiser of the Anti-Bullying Week campaign. Every year, the campaign aims to raise awareness of the bullying of children and young people in schools and elsewhere and to highlight the ways of preventing and responding to it. Whilst we are somewhat removed from the world of educating young people, we recognise that our working environments are the next step for them as they develop, and many will spend their careers working in the teams and according to the cultures that we are building.

We are by no means experts on bullying, but we know bullying doesn’t just stop at childhood – adult and workplace bullying takes place and can have an especially damaging impact not only on individuals but on whole teams and organisations. We wanted to highlight the campaign and share some thoughts on how building an effective team creates a working environment where people feel confident, supported and empowered (and, of course, not bullied!). Just as we recognise there are actions that can be taken to prevent reaching the dispute resolution stage, there are also actions that we can take as leaders to prevent the unhealthy cultures and environments that tolerate workplace bullying from developing in the first place.

Remember these key ingredients so that you can make sure you are doing more than just creating a team – you are building an effective one.

We hope this information has been useful, if your team needs support in strengthening those social competencies, please get in contact with us. If you are seeking support for workplace bullying, here is an online resource from CIPD, the Professional body for HR and people development.

* Humble Leadership: The Power of Relationships, Openness, and Trust, Edgar H. Schein, 2018

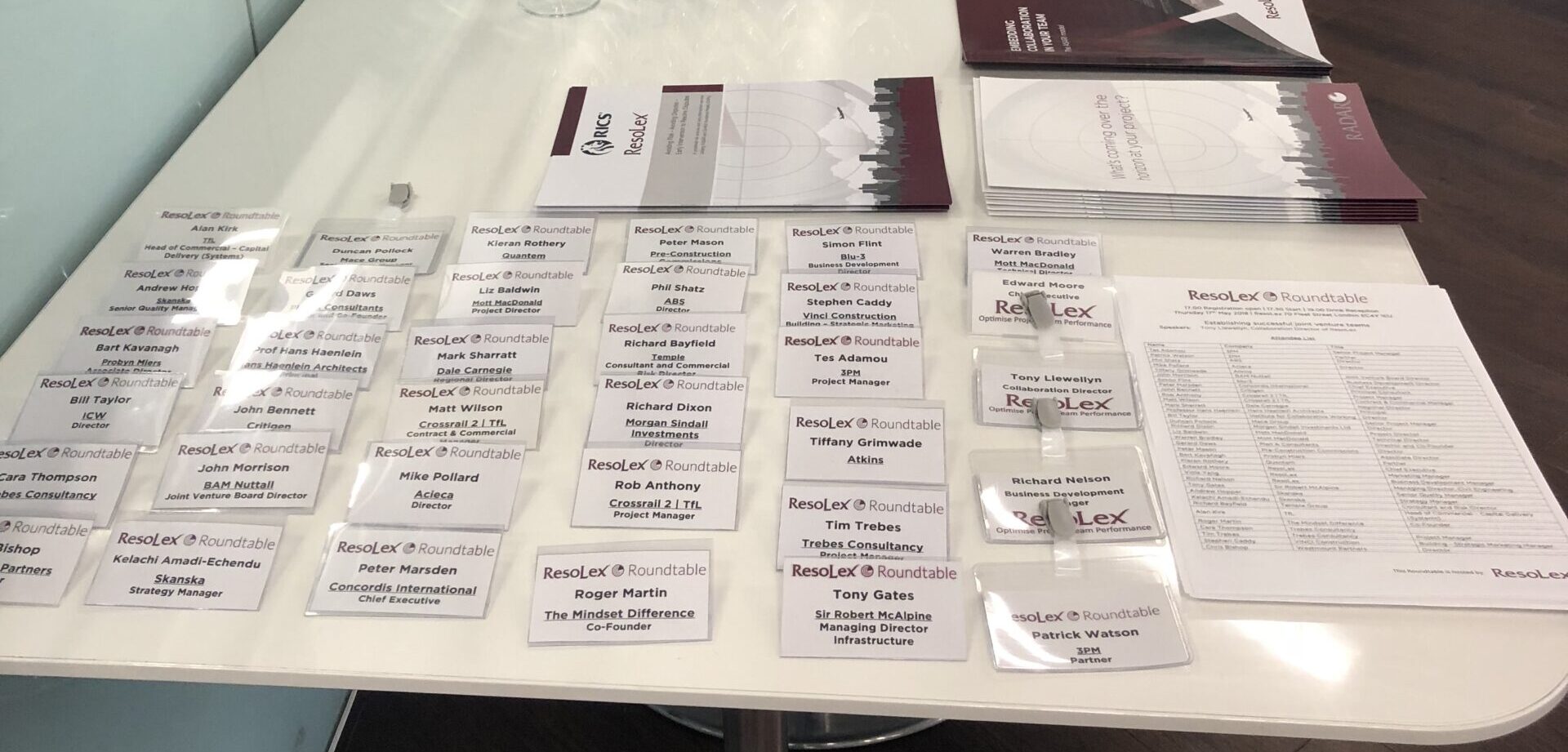

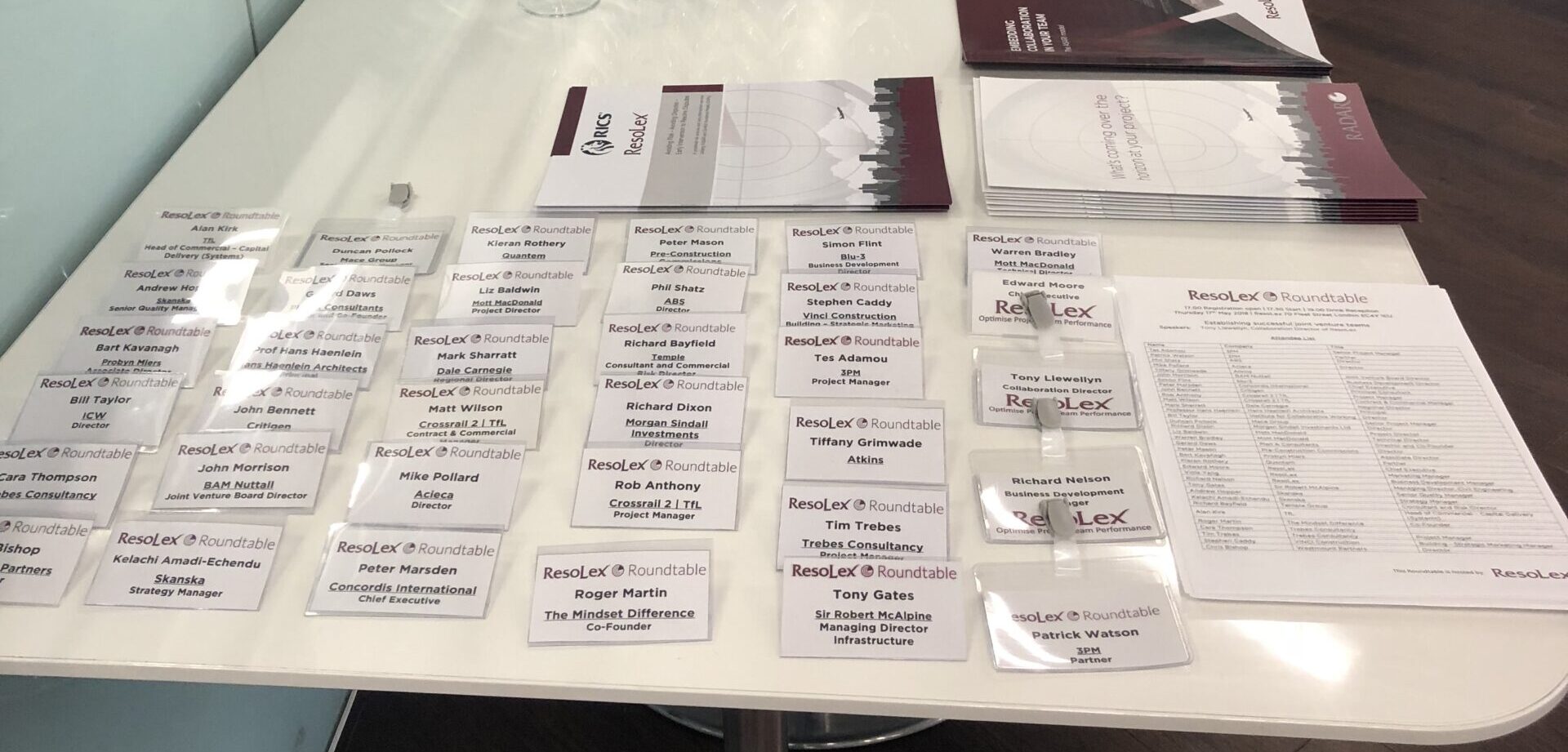

May 17, 2018 | Events, Roundtables

Speaker: Tony Llewellyn, Collaboration Director of ResoLex, Visiting Lecturer at the University of Westminster

This month’s round table meeting focused on the output of a research project that Tony has been working on for the last eight months. He has a long-standing interest in the dynamics of large project teams and the challenges of creating cohesive and collaborative groups working on construction projects. Recent experience in facilitating a number of workshops of two or more firms about to go into a joint venture highlighted the additional challenges faced when distinct groups of people come together. The common view is that up to 70% of joint ventures (JVs) fail to achieve their original objectives. Rather than focus on the reasons for failure, Tony decided to try and discover what actions and activities were put in place by the 30% of JV teams that got it right.

The research

The research project was based on twenty interviews with senior directors experienced in JV projects. The focus was mainly on construction projects but also included a property JV, some O & M ventures and a training partnership. The data were supplemented with the output from the 100 or so people who had participated in the JV workshops. The research also includes a literature search of scientific papers published over the last 20 years on the topic of successful Joint Ventures.

Tony summarised his findings into four key themes:

1. Partner selection

2. The role of the Governance Board

3. The role of the Project Director

4. Setting the leadership team up for success

Partner selection

The evidence collected from the research highlighted the importance of selecting the right partner when going into a JV. Most of the interviewees acknowledged that they would ideally work with a firm that they had done a JV with before. However, in the absence of a suitable past alliance, the key determinant was to find a firm with a compatible culture. This was therefore less a matter of working with the same people, and more a question of finding a culture where each party felt they could connect and communicate, irrespective of the personalities involved.

The role of the Governance Board

A high number of interviewees pointed to the need to pay attention to setting up the right governance board. The role of the group that maintain an oversight of the project team is usually prescribed in the JV agreement. All too often, however, the dynamics of having two equal sets of senior directors trying to work together on an occasional basis can quickly become dysfunctional. This partly arises because of the dichotomy of having to try and support the project team on the one hand, whilst also protecting their respective firm’s interests on the other.

The merging view from the research is that a strong governance board is typically well chaired, meets face to face when it can, has a mix of skills and experiences, but most of all comprises people who have a collaborative disposition.

The Project Director (PD)

The research highlights a number of success criteria for a JV project director, including:

- An ability to cope with complexity

- An ability to manage ambiguity

- Clear performance goals

- A stable management team

- Strong technical competence and industry knowledge

- Co-operative reward structures

One of the interesting features of a strong PD was the recognition that they needed to recognise two distinct leadership roles that were needed on very large projects. One is an ability to face outwards and manage the relationships with the client and stakeholder groups. The other is to have a strong emphasis on team integration and technical delivery. It was noted that it is rare to find an individual who excels at both. It was therefore important when selecting a PD to assess the particular needs of each project. Additional supplementary support could then be planned before it was needed.

Setting up the Project Leadership Team

The fourth success theme was the recognition that thought and planning were highly important when assembling the JV leadership team. The criteria included:

- Selection on ability rather than availability

- Senior roles are clearly defined

- No man-marking

- Homogeneity – similar age and values

- Heterogeneity – a variety of skills and experience

- Alignment to a common goal

- Cooperative disposition

There was also a consistent level of agreement on the need to invest time early in the programme to build relationships in each of the groups engaged in the JV. The presentation included with a quick run-through of the ASARI model developed by ResoLex for team development which is based on research into effective team performance. This model is illustrated in the diagram below.

The session concluded with a discussion from the floor around governance practices and the experiences different members of the audience had found in both successful and unsuccessful teams. The primary message is to avoid complacency and invest time and effort in planning how to make a joint venture achieve a successful outcome.

Feb 1, 2018 | Events, Roundtables

A Case Study from Surrey Highways and Kier Services

The session was opened by David Mosey who provided a short explanation of the FAC1 Framework agreement. For those not yet familiar with FAC1, it provides a framework for organisations to enter into an agreement that will enable and support the award of a number of contracts whilst not itself being a project contract. The agreement anticipates a situation where a client wishes to set up a longer-term partnership or alliance and needs an overarching document that covers:

- Joint planning and risk management

- Improved consistent working practices

- Encourages learning to be passed from project to project

- Achieves improved value through collaborative working

David used an example from a roads maintenance agreement, involving Surrey County Council, Kier Services and a number of specialist subcontractors. The agreement used an early prototype of FAC1 to help Surrey Council generate savings of roughly 15% from the original tendered contract as well as a number of additional benefits.

The FAC1 agreement is only 18 months old but has already been picked up by a range of public and private organisations who are investing in development programmes.

Nigel Owers then explained the background to its new Alliance program. Kier had originally won a tender for a 6 year highways maintenance contract in 2011, which gave Surrey the option to extend by an additional four years. Having successfully delivered the initial term of the contract, the council agreed with Kier to extend the contract to 2021. The extended agreement is intended to deliver continue additional value and innovation through the supply chain through revised and collaborative arrangements. The strategic goals of the Alliance are:

- Increased collaboration between SCC, Kier and the supply chain

- Achieve the objectives of the Surrey Business Plan

- Find a further 2.5% saving

- Develop a sustainable supply chain through to 2021.

Nigel ran through the re-procurement process and explained how the Alliance agreement was implemented. A useful illustration is a summary of what the Alliance members have agreed to do:

- Hold Core Group meetings;

- Adopt and participate in early contractor involvement (“ECI”)

- Share and/or improve working practices for the benefit of Surrey and the Term Programme

- Attend other framework review meetings as required in order to achieve improved value

- Implement social value proposals

Measurement and feedback are important elements. For example, the agreement sets out four success measures:

- Performance Review

- Social Value

- ECI

- Alliance participation

Nigel closed by acknowledging that the Alliance was still in a learning phase and that the parties were each still getting used to the new arrangement. It was interesting to note that those individuals who were part of the previous alliance programme were apparently comfortable with the open dialogue that featured in the first Alliance meeting. Those who were new to the format were much less certain as to how to make the adjustment from a transactional set of behaviours to the collaborative mindset required as part of this alliance.

Keith Coleman then presented the Alliance process from his perspective. His role is Head of Contracts and Supply Management at Orbis, an organisation formed to provide procurement services to Brighton and Hove, East Sussex and Surrey Councils. Keith explained the drivers created by the huge funding gap that all local government bodies need to close. They are therefore continuing to explore mechanisms that will enable them to gain additional value by setting up collaborative arrangements with key suppliers. There is consequently is a shift, both within local and central government, away from short term lowest price bidding.

Keith talked about the progression of different relationships to deliver better value from a procurement perspective. These range from category management and strategic sourcing through to supplier relationship management. For many procurement teams the Alliancing framework is a significant stretch requiring a new mindset as well as new processes and procedures. He nevertheless envisaged an additional stage where major buyers such as local government might take the Alliancing process to encompass entire markets.

For example, Surrey currently deals with 400 separate care home providers. He asked the room whether it might be conceivable that an Alliance framework could be used to find greater value from such a dispersed network? Keith did not suggest any answers but left the room with a clear sense that given the right mindset and the appropriate toolkit, much more was possible.