Oct 2, 2020 | News and insight

In Part One of this article I introduced a concept I called the Collaboration Fallacy, which is an inaccurate assumption that multiple teams engaged in a major project will automatically work together in the best interest of the project. My purpose in articulating the idea of the Collaboration Fallacy is to nudge project leaders to recognise that humans do not naturally work as happily integrated units. The project culture in which they operate must encourage them to do so. The concept is an extension of the more widely acknowledged phenomenon known as the ‘planning fallacy’, initially identified by Daniel Khaneman and Amos Tversky. Khaneman and Taversky observed that humans continually underestimate the time needed to complete a project despite the information being available to them that would lead to a more accurate answer.

The key point that I tried to emphasis in the first article is that if project leaders were to take the time to look more closely at the factors that bind or disrupt inter-team relationships, they would take a different view as to what was needed to build a successful team of teams. This is particularly important when stepping up into complex project environments where the interactions between groups of people become one of the most troublesome variables. I have noticed however, a high level of complacency in many senior teams at the start of a large project, where the predominant belief is that everything will be fine, and any problems that arise will work themselves out. Once the behavioural norms are set however, they are very difficult to change.

The challenge, therefore, is to find some mechanisms that will help project leaders avoid this naïve tendency and look more closely at the challenges ahead. Logically, we should start with learning from our past experience and that will help avoid making the same mistakes again. There are thousands of project case studies in the public domain which identify the problems created for teams when working in projects with high levels of ambiguity and frequent change. Auditors and analysts often identify a lack of planning or forethought which might have avoided significant difficulties downstream. I have found, however, that stories of past failure often carry little weight when thinking about future projects and programmes. The prevailing view is that ‘this project is different, so those problems will not occur’. In my research, I have found a richer source of knowledge and learning to come from asking my interviewees to describe a project that went well, rather than one that went badly. This is often an interesting challenge, as successful large projects are much less common than one would think.

The question as to what went well, and why, is intended to draw out the factors that actually turned out to be important to success, rather than the more superficial elements that are more commonly used when planning a project. I have found almost without exception that when a project is considered in hindsight to have been successful, time and resources were spent focusing not just on the technical and commercial challenges but also the social components of team development and interaction.

One simple solution to avoid falling prey to the Collaboration Fallacy is for the senior team to set some time aside in their planning sessions to ask each other to tell a story of what made a past project a success and then crucially, what learning might be taken into the current project. Stories are immensely powerful in helping humans learn; they resonate at both an emotional as well as a cognitive level, so that we remember more of the detail, and attach greater meaning to the experiences of the protagonists. As human beings we are more likely to react to someone else’s story than we are to bullet points in a PowerPoint presentation.

The beauty of this approach is that it diverts the discussion away from the instinctive focus on technical planning which tends to dominate most early senior team meetings. Instead, the question allows each person to slow their thinking and reflect on the past. Once everyone has had a chance to contribute, the session could move onto another crucial question; “What has to go right for this project to be successful?” (It is important to note that what needs to go right is very different to the question of what could go wrong.)

Setting time aside to plan for building positive relationships and interpersonal trust can be distracting when a newly formed team really just want to press on with the process of delivery. The payoff downstream is however potentially huge, particularly when trying to work in a complex environment. So, as you move into your next project, one of the key questions to ask your team is ‘are we in danger of falling for the Collaboration Fallacy here, and if so, what are we going to do about it?’

Tony Llewellyn

Oct 20, 2020 | News and insight

Delivering projects is a human activity. Generating something new from ‘thin air’ requires groups of people who are able to conceive, plan and then execute a series of complicated activities that will, in some form or other, enhance the lives of other human beings. Large projects require the input of many highly specialised skills, which are of limited value in themselves, but are of significant worth when combined with the skills of others. It is this combination of applied skills that lead to success. Project teams need intelligence, or more particularly three distinct types of intelligence.

- Technical intelligence – the knowledge and awareness of how to find the solution to a particular problem or opportunity.

- Commercial intelligence – the knowledge and awareness of issues around money, contracts and the identification and management of risk.

- Social intelligence – the knowledge and awareness of how humans behave in groups and teams.

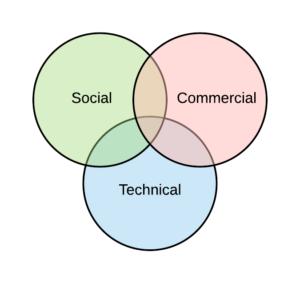

Large projects require lots of people. Despite advances in automation, we remain a long way from having robots to design, manage and deliver complex engineering software, logistics or construction projects. These enterprises require human expertise and ingenuity to make them happen. As illustrated in the diagram below, there is a sweet spot at the centre of the Venn diagram where these three elements combine to form the rounded capability to lead and manage a major project. When assembling a project team, we tend to value specialist technical and commercial skills in others because they cover for gaps in our own skill or knowledge set. Adding social intelligence to the group, however, tends to be seen as much less important.

Social intelligence

We often use the word ‘dynamics’ to describe how people interact when they are together in a group or team. The word dynamics actually means ‘forces of change’. We tend to use the phrase ‘human dynamics’ when talking about how people interrelate when they come together as a group or a team. So human dynamics are essentially the forces that create or destroy the momentum of interaction between groups of individuals.

The problem is that people are messy. Humans are driven by a complex series of emotional reactions that are genetically hardwired into us to thrive and survive. Our behaviours are driven by motivational factors that are often not visible to others and can often be difficult for others to comprehend. To understand others and then have them understand you is an essential human skill. The ability to first understand others and then be understood by them is often referred to as Social Intelligence. This is a term used to describe a degree of awareness of the human interactions between oneself and others and also between others.

The concept of Social Intelligence has a variety of possible definitions but at its simplest, it is ‘an ability to get along well with others and to get them to co-operate with you’ . Daniel Goleman (2006) argues that whilst IQ is something that you are born with, social intelligence is regarded more as a learned skill, than a genetic trait. This leads us to the question that if social intelligence is an essential component of project success, then why do professional bodies pay so little attention to its development?

My observation is that there tends to be a tacit assumption in many teams that everyone on the team will automatically have the social skills needed to get along well with each other. This often turns out to be a significant misjudgement. Whilst humans have evolved to work in groups, left to our own devices we also have an amazing capacity to find reasons to disagree and dislike other people or groups. As projects have got bigger and more complex, it is clear that future generations of project leaders are going to have to take the development of their social intelligence more seriously.

Positive social interaction in project teams cannot therefore be left to chance. In just the same way as the technical and commercial competencies, there are methodologies for building strong social bonds. Those methodologies need to first be understood, learned and then practiced.

Learning and development

So if Social Intelligence is a learned skill set, the next question is how and where to acquire it.

The prevailing belief in universities and colleges appears to be that the development of social skills should be left to future employers. The problem in deferring the development of these skills is that too much effort is spent in remediating bad habits and rebuilding confidence, rather than providing the more advanced social competences needed to help individuals and teams thrive in a complex environment. It is interesting to note the outcome of a survey of teachers, reported in an article in the Times Literary Supplement dated 30 August 2017. The article highlighted the statistic that 91 per cent of respondents felt that schools should be doing more to help their pupils develop teamwork and communications skills.

There is a tendency to call the ability to understand and communicate a ‘soft’ skill, the implication being that learning how to connect with other people is an imprecise art rather than a precise process. I believe this is an outdated description emanating from a time when managers lacked both the knowledge and the need to recognise the practice and process of efficient and effective team development. The other argument for degrading social skills to the category of ‘soft’ is a belief that they cannot be measured and therefore cannot be managed. This again is simply lazy thinking. There is no difference in my mind in assessing someone’s technical, commercial or social capabilities. It is simply a matter of choosing the metrics and then making the effort to collect the data.

Organisations will periodically invest in soft skills training in areas such as presentations, negotiation, time management and communication.

These are active elements which reflect the ‘tell’ mindset predominant in western organisations. Social intelligence is a wider concept, which involves more than just what one person says or does. To be able to influence what happens in a team, you need to understand what is going on, not only when the individuals react to each other and how they collectively respond to events that impact on the team. Social intelligence learning therefore includes areas such as:

- Systemic thinking. Seeking to identify all of the different factors that have created a situation. It involves techniques to look at a problem or issue from a number of different perspectives.

- Understanding group dynamics. Learning how to ‘read the room’ to gauge what is happening underneath the surface behaviours of the team.

- Influential enquiry. Controlling and steering conversations through the use of skilled questions.

- Conflict management. Managing difficulties and problems by creating an atmosphere that encourages dialogue rather than heated debate

- Psychometrics. Understanding others by learning to recognise their motivations and preferences and adapting your messages so they recognise your point of view more quickly.

- Sensory awareness. Knowing how to really listen to what others are communicating not just in words but in posture, eye movement, facial expression and pace of voice.

- Reflection. The habit of methodically taking time to think about recent experiences and consider what happened, why it happened, and what to do the next time a similar situation occurs.

The skills set out above can be taught but as with any skill, must be practiced to become proficient. These skills must be learned and developed in the same ways one acquires technical and commercial skills. The initial information can be acquired in the classroom, or from books. A good place to start would be to check out my website, www.teamcoachingtoolkit.com. The real learning only comes however, when trying to apply this knowledge in a real-life situations.

Managing Behavioural Risk

This article has focused on the need for project leaders to pay attention to the social or people based factors in addition to the technical and commercial challenges that every project must deal with. Successful projects almost always feature successful teams where collaborative behavioural norms had been embedded early in the project life cycle. Ineffective teams will always struggle to deliver on their promises and so anyone studying the risk of default must pay attention to the dynamics present within the core team.

As projects continue to grow in size and complexity paying attention to the level of social intelligence in you team may well be the difference between success and failure. I would therefore urge any leader looking for a better way of reducing the risk of project failure to explore the investment in developing the social competences outlined above. A team with the full range of strong technical, commercial and social skills is much more likely to build a success story.

Tony Llewellyn

References

- Golman, D (2006) The new science of human relationships, Random House

- Ward H, (2017) Teachers rate soft skills as more important than good grades. Times Educational Supplement, 30 August 2017. https://www.tes.com/news/school-news/breaking-news/teachers-rate-soft-skills-more-important-good-grades (accessed on 5 Jan 2018)

Oct 20, 2020 | News and insight

The COVID-19 crisis has forced teams to continue working together using electronic media. Many organisations are finding that at least temporarily, they can operate on a virtual basis, giving much credence to the argument that remote working is at least as effective as office-based operations. However, a question that has been playing on my mind over the past three weeks is; how much knowledge are we missing from the part of natural communications process that might be called our ‘peripheral vision’? Peripheral vision is how I would describe what enables us, often accidentally, to discover that someone else has found a solution to a problem we are struggling to solve, or those moments we find a connection to an option which we were previously unaware of. A couple of simple questions highlight my point:

- How often do you gain the most valuable insights while having a conversation over making a coffee prior to a planned meeting, rather than during the meeting itself when following a pre-set agenda?

- How often within an office environment do you hear a snippet of a conversation which makes you stop what you are doing and go and find out more?

I sense that this information gap is going to increasingly impact our ability to move projects forward as the return to working in an office environment looks even more distant. My concern is whether the working habits we are developing at this time are nudging us unintentionally into siloes, where connection and communication across sub-team boundaries become limited. So, what mechanisms could we try and develop to help replace this missing source of information in a distributed team? I can think of three potential areas:

- Behavioural – Part of the answer might be to become more expansive in our thinking about our current work and how it might be used. Who else might find it useful to know what we are working on and the challenges we are struggling with?

- Becoming a ‘learning team’ – The benefits of recycling learning back into a team are a well understood feature of high performance. Adopting the habit of regular review of what has happened and what could we do to improve, will push a team to extend their peripheral vision. By pausing to reflect, team members increase their chances of thinking laterally to explore new connections.

- Explore technology – One example that I am interested in exploring further is the use of software to analyse communications and connect people within an organisation who are not already connected but are having conversations with others about similar topics. The increase in the availability of free-text theming software could really support knowledge management in a new way.

My purpose in writing this short article is not to prescribe the answer, but to try and stimulate some discussion about how we continue to adapt our working practices to ensure we can be as effective working in distributed team. I would therefore love to hear your thoughts and opinions on this issue.

Edward Moore